A musical friendship on Boar’s Hill

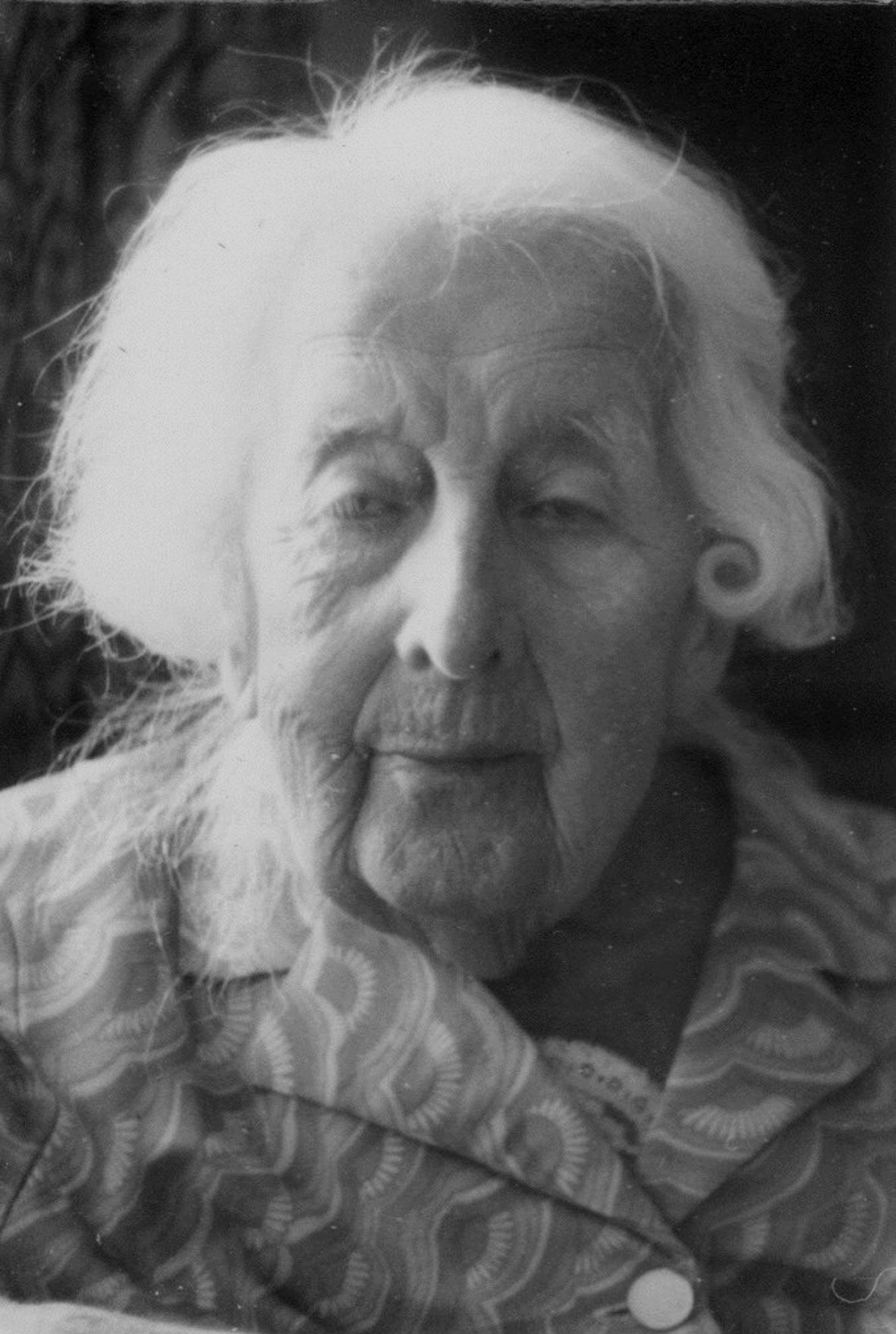

Sybil Deane Jackson (1877-1976) was Lennox Berkeley’s godmother and stepdaughter of Lennox’s uncle, the scientist Randal, Earl of Berkeley. Dr Michael Rice recalls a musical friendship

Sybil Jackson befriended me in 1967 when, in defiance of the three-mile rule, I was living on Boars Hill as an undergraduate, and she was living at Foxcombe Cottage, near Foxcombe Hall, where she’d been brought up with her step-father Lord Berkeley, before he inherited the castle and re-married.

I had arrived on Boars Hill in July or early August to lodge with a Mrs Hamilton (who published free verse in The Tablet as Lydia Wickham; however Sybil later told me she had discovered that her married name had originally been Jackson until she changed it to something classier). To the wider world, Mrs Hamilton was a Bentley-driving snob, but she lived in genteel poverty in only one room of a seventeen-roomed house, with a wheezing peke; she had long been widowed, had lost a son to TB during the war, and her daughter (who was with the Colonial Office in, Nigeria) wore a permanently pained expression following a teenage summer holiday appendectomy under nothing more than a local anaesthetic, ‘because the French doctor wanted to improve his English’.

The good thing about my room was that I could see for 17 miles across the Vale of White Horse. The bad thing was a piano that couldn’t have been tuned for 20 years. I think Mrs Hamilton supposed that by introducing me to Sybil any invitation to play the piano at Foxcombe would give her ears a rest. I was successfully palmed off, and silence returned to Monkton House.

It was shortly before her ninetieth birthday when I first met Sybil, after which I saw her at frequent intervals for five years and then much less frequently until six months before she died in 1976. The routine was an invitation to ‘luncheon’ – she was true to her generation – and then two-piano duets until tea-time, after which we played for a further hour or so before adjourning for a drink – she was fond of Cinzano – and then I cycled home. The walls of the L-shaped music room had absorbed much greater things than my playing: Sybil told me that Rudolf Serkin had performed there during the war (and so, I think, had the Busch Quartet).

I remember the substance of many of our conversations. No doubt there were oft-told stories: of Robert Bridges disappearing from the tea-table at Foxcombe Hall and being found lying on his back in the long grass in the orchard; of the archaeologist Arthur Evans short-sightedly eating both the fish on his plate and the paper case it had been served in; and of watching Debussy conduct and observing his ‘unusually square head’. She also remembered playing the incidental music on a harpsichord (or perhaps a spinet) for a play by John Drinkwater in the garden of the poet John Masefield, and regretting that few members of the audience had been able to hear her contribution in the open air.

Sybil was the daughter of a professor of composition at the Royal Academy of Music in London and had studied singing with the great Polish bass Édouard de Reszke and piano with the composer and pianist Carlo Albanesi. Her own voice, certainly in the inter-war period, had been a light soprano and she had taken the soubrette roles in Sir Hugh Allen’s summer vacation Mozart opera productions at New College. (Would you have imagined that such a dedicated Mozartian liked to watch the wrestling on television on Saturday afternoons?)

She told me that when Lennox was a little boy – about three years old or so – and she visited him and his parents at Melfort Cottage in Hamel’s Lane, he would implore her to ‘Play piano’. Her customary response was to sing An die Musik to her own accompaniment: and that, she thought, was the beginning of Lennox’s love of repeated chords.

Like Lennox, Sybil was fond of dogs. Although she didn’t keep a dog of her own, a Scottie used to pay frequent visits from a house about a hundred yards down the road. On the one occasion that I met Lennox, with Freda and Michael, at Sybil’s house, they had brought their black Labrador Prince with them. He was clearly a favourite with Sybil, but I think it was Lennox who expressed regret that people no longer gave their dogs ‘the old names’.

I must have taken a flute to Foxcombe Cottage one afternoon so that we could play Lennox’s Sonatina [for Treble Recorder or Flute and Piano]. After Sybil had accompanied me the first time round, she went to the music cupboard and fetched her treble recorder – a simple, 1930s instrument on which you had to half-hole the bottom F sharp and G sharp. She said that she used to play the sonatina on this instrument but she had run out of puff and it was my turn now. So we played the piece again, with her recorder instead of my flute. I kicked myself, because I had exchanged post cards with the American recorder maker Friedrich von Huene only a few months earlier and decided that I could not afford one of his instruments. In those days, by living on porridge for a couple of months, I could have done it.

Not surprisingly, Sybil often spoke of Randal Berkeley, who had clearly been the most important person in her life. However, he was always ‘my stepfather’, despite stories I heard later which suggested a closer relationship. She had had admirers, of course; we once played a waltz dedicated to her by one admirer around the turn of the century. She only once gave me an indication that Lord Berkeley’s interest in her might have been physical, but she told the story with such bemusement (as I supposed) that I thought it better not to let on that I saw its implications. Berkeley liked to have salad dressings mixed at the table. The ingredients were poured into a gas jar from his laboratory, and then Sybil was required to stand by the head of the table and shake them. I’d guess that her bodice was not entirely whalebone, and that Berkeley’s guests appreciated this performance.

One afternoon, over tea, Sybil showed me a set of photographs of a house that Berkeley had owned at Aix-les-Bains. He had forgotten this house, she said, when he made a will, and it had reverted to the French state on his death – much to her regret, as she had hoped that he might leave it to her.

Sybil told me once that she believed she had been the first woman driver in Oxford. Her stepfather’s chauffeur had given her a morning’s instruction in the drive at Foxcombe Hall, and in the afternoon she had driven herself into the city and parked in St Giles. The journey home was not so smooth. Sybil said that she lost control of the steering just as she drew level with the Post Office (on the right-hand side of St Aldates, travelling away from Carfax), the car swung round to the offside and came to rest with its front mudguards – which protruded well ahead of the bonnet – against the Post Office wall. This created a small enclosure in which she found she had trapped a man pausing to check his pocket-watch by the Post Office clock. She said that she had never forgotten the expression on his face when he lowered his glance from the clock and looked around him.

During the First World War Sybil thought she should ‘do my bit’, so she joined a Voluntary Aid Detachment to provide medical assistance at the Radcliffe Hospital. When put in sole charge of a ward on her first night shift, she was asked to make tea for the soldiers. It was not a success; she had never made tea before. So she asked a more experienced colleague how she should make a satisfactory pot of tea, and on her next shift, Sybil threw a handful of washing soda into the pot, and this won the soldiers’ warm approval.

In my time two visitors to Foxcombe whom I was sorry not to meet were a German octogenarian and her daughter. (This might have been in 1972.) Reporting their visit a few days later, Sybil told me that she hadn’t immediately recognized either of them. ‘But don’t you remember me?’ asked the mother. “I was your maid 70 years ago.’ Sybil did, of course, remember; and it doesn’t surprise me that she could inspire such loyalty over the decades; she was totally without side. The German ladies brought her a gift: the urtext edition of Beethoven’s piano piece, Rage over a lost penny. As Sybil didn’t much care for Beethoven she gave it to me, and I have it still. But the memories are what I treasure most.

In old age, Sybil maintained a great zest for life. Freda might remember the dignified way in which she would come downstairs on her bottom, one sedate step at a time, while continuing a serious conversation. She was a dear friend, and possibly the least judgemental friend anyone could ever have had. If she meant this to me, what she meant to Lennox (and what he meant to her) is inestimable.