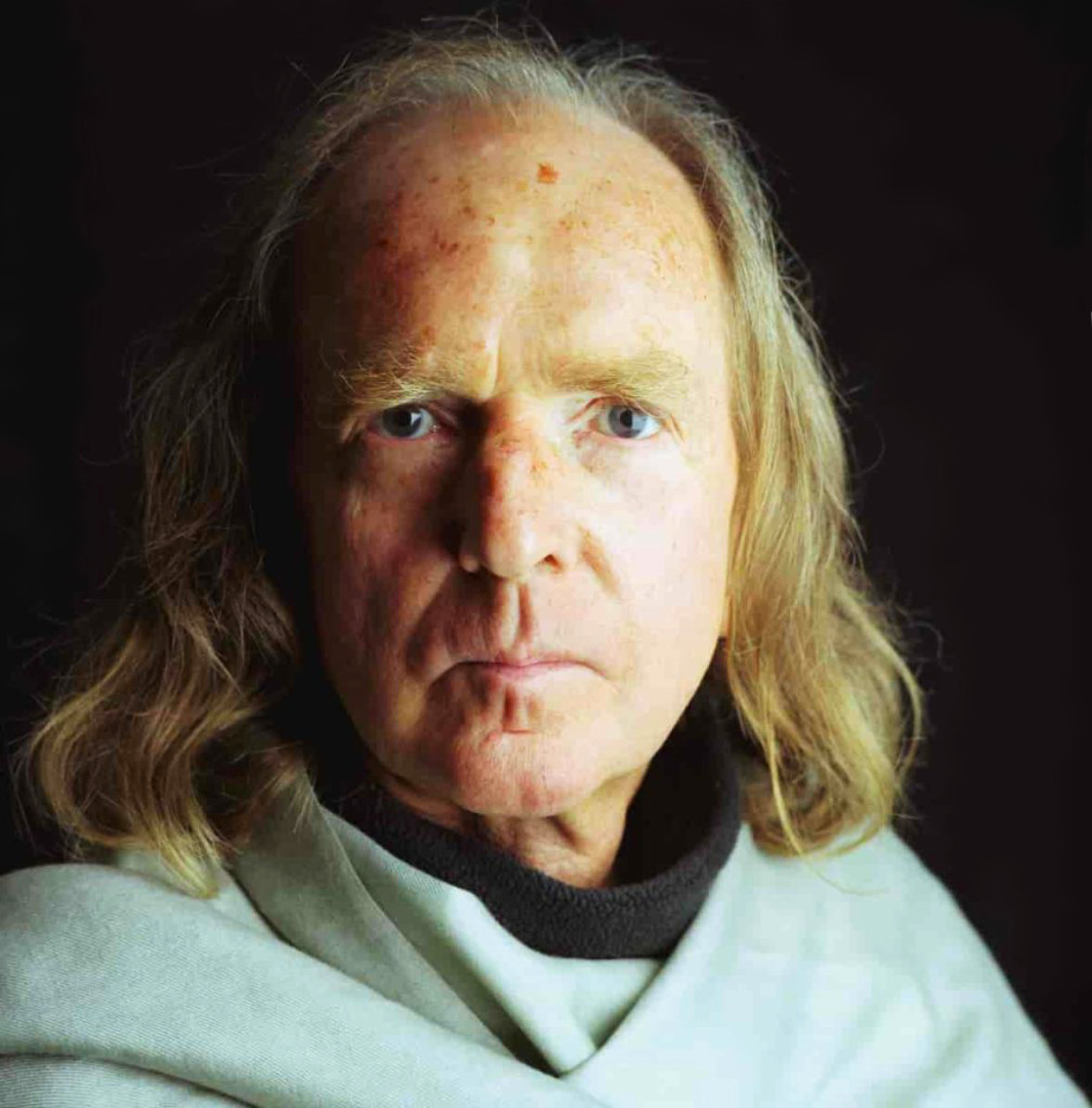

Sir John Tavener obiturary (28 January 1944—12 November 2013)

Michael Berkeley remembers a friend, colleague and patron of the Lennox Berkeley Society

Thanks to the closeness of John Tavener and my father – both as student-and-teacher and as spiritual journeymen – I had a life-long connection with John, who died last November aged 69. I so well remember him, his lankiness emphasised by his schoolboy shorts, coming to see Lennox for advice on his music, when I was a child. Later, when he was still more of a lovable bean-pole, John came to study with Lennox. His gifts, his sheer unusualness, were evident from a tender age and he was a formidable pianist.

If Lennox was at times bemused by the inspired eccentricity of John’s ideas, he always maintained that there was something very special there. In a television interview in 1970, he said he could not follow everything that John was then writing: ‘It’s got a little beyond me in a way, because I’m of an older generation, but I always thought him one of the most gifted young people that I’d ever had [to teach].’

For John, Lennox’s sweetness of disposition and his love of the sacred were, I think, important anchors in a confusing world. My father’s faith as a traditionalist Roman Catholic was, in his view, ‘the essence of the man’, and it often caused what John saw as ‘a misplaced humility’, yet he believed that Lennox’s Latin settings reveal a truth and a conviction which come from what he called ‘the one thing needful’. This was particularly apparent in the Stabat Mater, which John thought ‘a work of profound beauty’. Whenever I met John in later life he would enquire with evident affection after Lennox and his work.

Good teachers do not want their students to copy them, but merely to absorb the knowledge which will allow a young composer to release and realise his, or her, own ideas. It may be no more than a conversation about religion or philosophy that makes the connection, or it could be an enthusiastic play-through of a Bach cantata or a Monteverdi madrigal. Certainly that was Lennox’s experience with the great Nadia Boulanger, and he not only practised that method with his students but, in John’s case, he suggested that he might profit from going to Paris to study with Mme Boulanger.

How John’s composing voice might have been changed by that experience we will never know, but I doubt that any teacher could have altered the marvellous maverick in John. He was a wonderful mixture of certainty and doubt. If I said to him that I loved a piece of his that I had just heard he would say disarmingly, ‘Did you really?’ Yet only a single-minded creator could have forged those early and extraordinarily original pieces like The Whale, Celtic Requiem, In Alium and Ultimos Ritos – and then, like Arvo Pärt, renounce that direction for a sacred purity, a language that relied on the spirit of mantra but is actually more complex than it sometimes sounds. Aspects of phasing technique that had interested him in the work of the avant-garde are to be found in the rhythmic and phonic layering of his choral works. But that John could write something of the greatest, and most beguiling, simplicity is nowhere more apparent than in his hugely popular carol, The Lamb. Even here, though, there are harmonic and idiosyncratic twists that make it unusual.

I sometimes struggle – and I think Lennox did too – with the repetitive nature of music like The Protecting Veil, but just as I am about to lose my concentration, some insidious worm of hypnosis keeps me tuned in: almost against my better judgement, I find myself wanting to hear some particular phrase again. It is this unrelenting power of conviction, which, when handled by an alchemist of space, irresistibly draws the listener in.

In 2007 I went to Istanbul with John and friends for a performance of The Beautiful Names, his musical meditation on the 99 names for Allah - and here we were back in familiar Tavener territory: over the top, but somehow right. It was all the more striking for its being set in a de-consecrated mosque, and hearing it in that most potent meeting-place of East and West, with John and members of his family, was to reach the heart of what inspired his creativity - the coming together of belief and ritual in a passionate outpouring of musical worship. Were it not so manifestly written in awe of the Almighty one might, as with some Messiaen, view it as an indulgence.

John never strove to be popular. He wrote what he wanted to write, and he was fortunate that it struck a chord, not only because of the music’s beauty, but also because of its quest for, and ability to create, an inner silence, an inner peace, a place of submission and reflection. In an increasingly busy and noisy world those qualities sounded a note of profound resonance for millions of people.