Berkeley’s orchestral ‘Divertimento’

Adam Pounds writes about Berkeley’s wartime orchestral score ‘Divertimento’

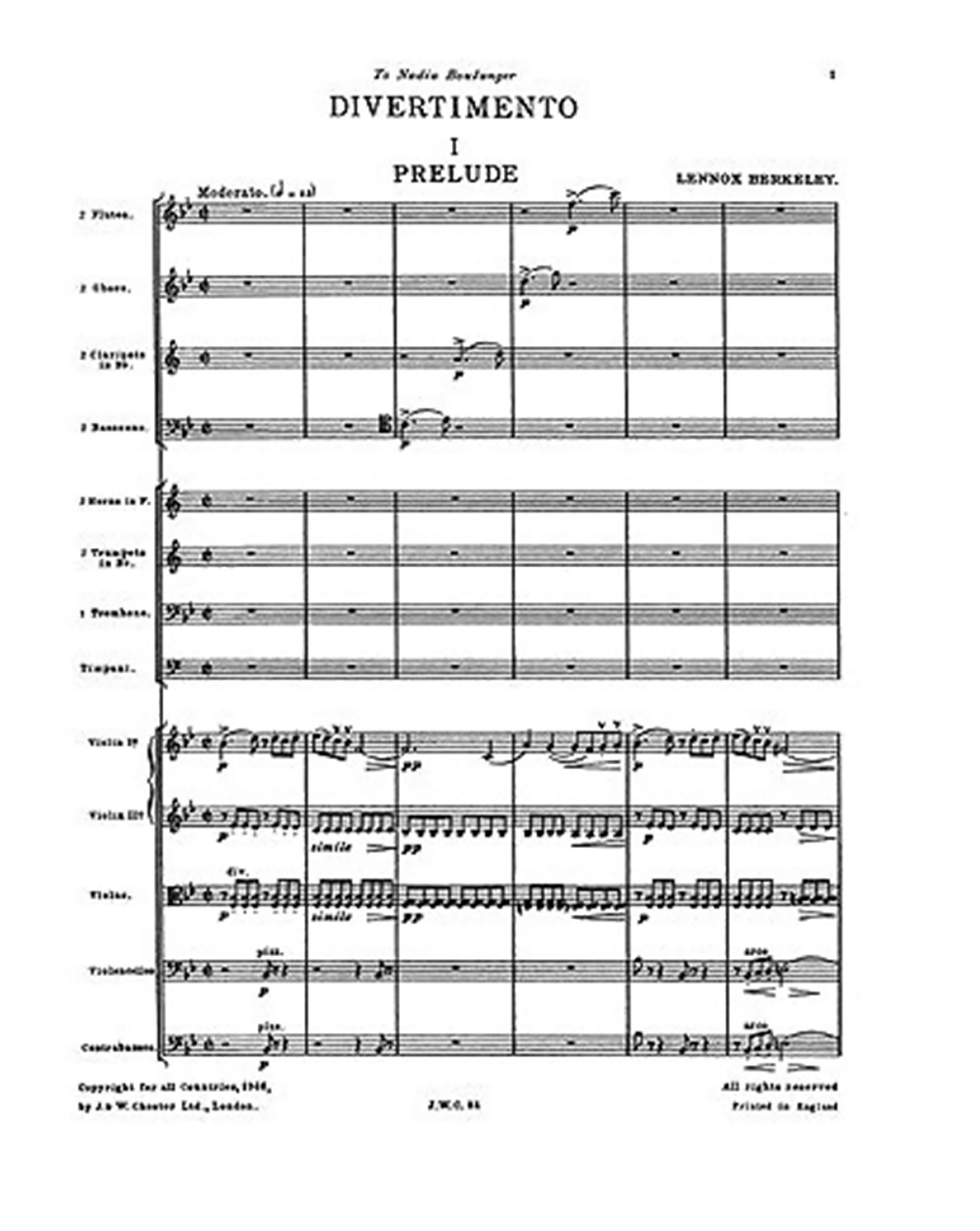

Last summer I had the great pleasure of conducting a performance of Lennox Berkeley’s Divertimento in B Flat in Cambridge to a very appreciative audience. Commissioned by the BBC and dedicated to Berkeley’s teacher, Nadia Boulanger, it was first heard in a BBC broadcast from Bedford [the BBC’s wartime home] on 1 October 1943 in a performance by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Clarence Raybould.

It is a work that I had been meaning to include in a programme for some time. I had already performed Berkeley’s Sinfonietta twice, encouraged in part by the available recordings. However, for me the Divertimento proved to be a stronger work which is full of interest. In addition to the standard chamber orchestra of the early nineteenth century, Berkeley adds a part for solo trombone to great effect. The piece is well suited to the amateur as well as the professional orchestra, and so it was a natural choice for the Academy of Great St. Mary’s, which I conduct on a regular basis.

One of the things I have always found most striking in Berkeley’s compositions is the economy of his orchestration. The light, transparent textures that often give way to strong forte’s look as if they are going to be underwhelming. Nothing could be further from the truth. A fine example of this can be found at the beginning of the first movement of the Divertimento. This lovely ‘Prelude’ (moderato) opens with the main graceful and lyrical theme presented in a Mozartian guise, played on the strings with gentle interjections from solo wind instruments. This could easily pass as chamber music. However, the orchestration at bar seventeen underlines Berkeley’s confidence in presenting us with a more forceful musical statement. The fine contrast is achieved by the gentle opening which provides the perfect foil to the forte section. This really is a case of ‘less is more’, and it’s confirmed by a comment of the leader of the orchestra, David Richmond, who told me that Berkeley always produces a clean, uncluttered sound, even while at times achieving considerable intensity.

The second movement is very strong. From the beginning we are submerged in a different sound world. Gone are the sunshine and sparkle of the opening ‘Prelude’, for in this haunting ‘Nocturne’ we are introduced to a very different tonality – almost Bartokian in style, and reminiscent of his ‘night music’. The movement opens with an ambiguous chord held on the cellos and violas formed by the notes of B flat, E flat, A and F sharp. The high solo bassoon enters with a simple, beautiful theme relished by my bassoonist Nicky White, who said ‘its strange beauty knocked me sideways.’ However, it isn’t long before Berkeley introduces a lyrical theme at figure 2. This is first stated by solo clarinet over a gentle ostinato in the strings, which is gradually developed over some twenty-five bars before reaching a heartfelt climax at figure 5. The progressive thickening of texture and growing intensity is typical Berkeley and can be found in other works – notably the finale of the wonderful Serenade for Strings.

The third movement, ‘Scherzo’, is substantial and would be just as at home in a full symphony. Once again, the scoring is light and confident. The wind players in the orchestra particularly enjoyed this, finding it both satisfying and challenging to play. Berkeley makes very effective use of cross-rhythms to drive the music forward, as we can see just before fig.10. This is something that I myself use as a composer, and I thank Lennox for his influence here. The trio section (meno mosso), based on block chords with interjections from different sections of the orchestra, is simple but effective. The musical material is quite sparse, and it relies on getting the right balance, particularly in the woodwind.

The ‘Rondo’ finale is a joyous movement, and here we see Berkeley composing with his Gallic flair. The main theme is uplifting and, as David Richmond observed, it includes exchanges of ‘Haydnesque good humour’. One of the most effective parts of this movement is the section marked Un poco meno vivo which appears at figure 11. It is a lovely, schmaltzy blues with an engaging theme built on falling chromaticism. When we first rehearsed this, it reminded the orchestra of an evening in a night club; perhaps this harks back to Berkeley’s Parisian days with his friend and mentor Ravel. After a short accelerando passage, we hear the return of the main theme and the piece ends with a flourish.

During my studies with Lennox in the 1970s, he never referred to the Divertimento but tended to concentrate on his chamber music as models. Perhaps because of his own modest disposition he would usually put up a score of Mozart as a good example of clean, balanced orchestration. Of course, he wasn’t wrong, but I could have learned a great deal from the Divertimento.

It’s a great work to conduct and it’s gratifying to see how well-received it was by the performers and audience alike. Rehearsals can be a real journey of discovery. The final performance has to give a clear picture of the composer’s intentions to the audience, and the experience of the players in engaging with the work in rehearsal, and getting to know it more intimately, can lead to an even deeper appreciation. Lennox presents us with a score that is clear in intention, and I found that being faithful to his directions in the score was the best approach. Knowing the man also helped enormously, and made me feel more closely connected with the music.

The Divertimento is a work that delivers on all fronts. It is beautifully balanced and coherent in its overall structure, with each movement complementing the next. Emotionally, it is not over-stated anywhere and yet the climaxes are strong and moving. In it Berkeley expresses different sides of the human psyche – exuberance and strength in the first movement, and considerable darkness, tempered with bitter-sweet phrases, in the ‘Nocturne’. Berkeley shows us his playful, good humoured side in the ‘Scherzo’ and this continues in the ‘Finale’.

It is clear to me that this is a quality opus that needs to be performed a lot more. It tends to be overshadowed by the popularity of the Serenade for Strings, but the Divertimento is easily its equal. For those who would like to get to know this work, Berkeley himself conducts the London Philharmonic Orchestra in a recording on the Lyrita label (SRCD226). It can also be found on YouTube in performances by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Igor Buketoff in 1968, and by the London Chamber Orchestra conducted by Anthony Bernard in 1948.

The players of the Great St Mary’s orchestra have already expressed a desire to include the Divertimento in another programme, so I look forward to returning to it. It’s a great piece in its own right, but it also combines extremely well with repertoire from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.