Why I like Berkeley

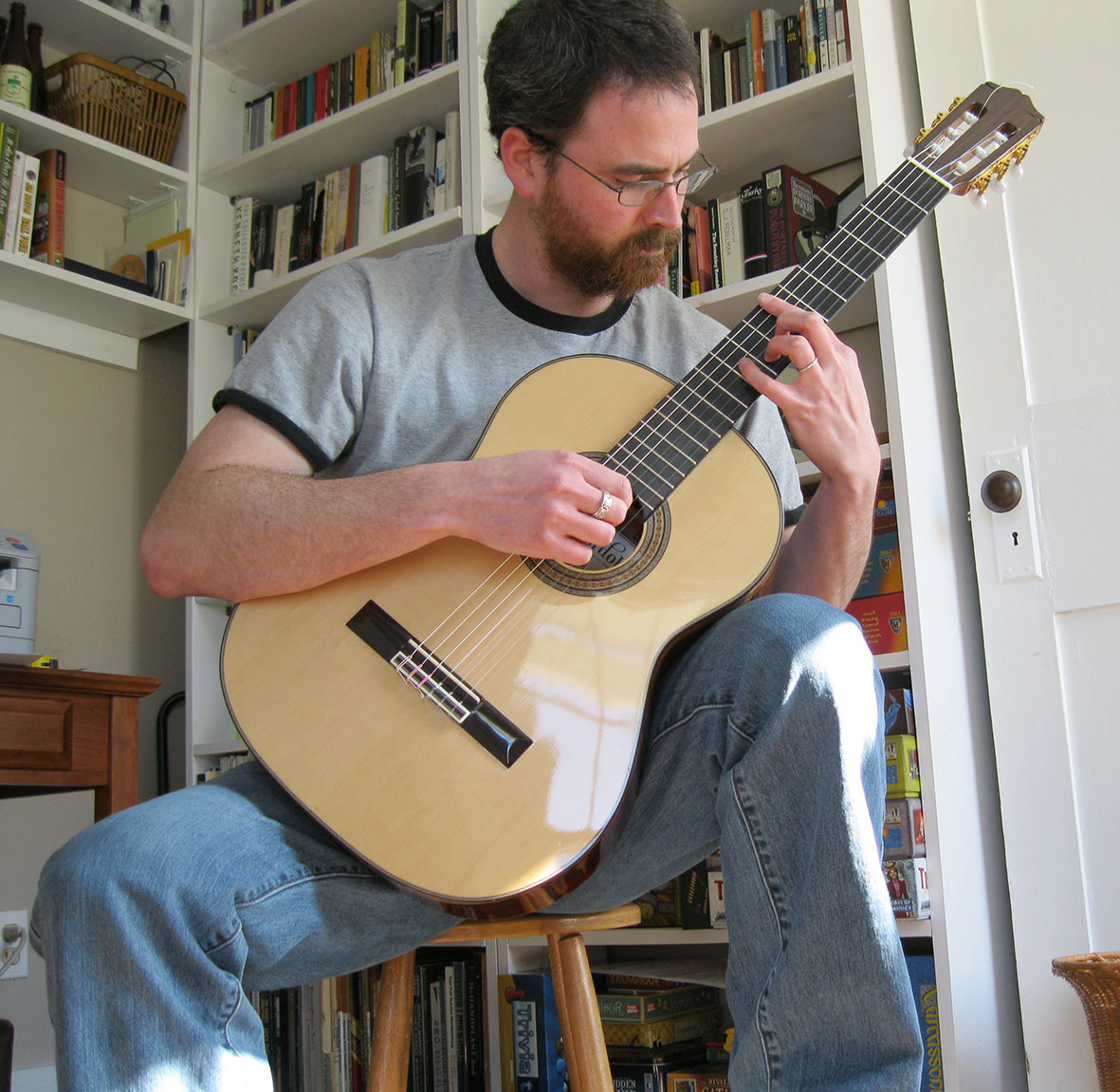

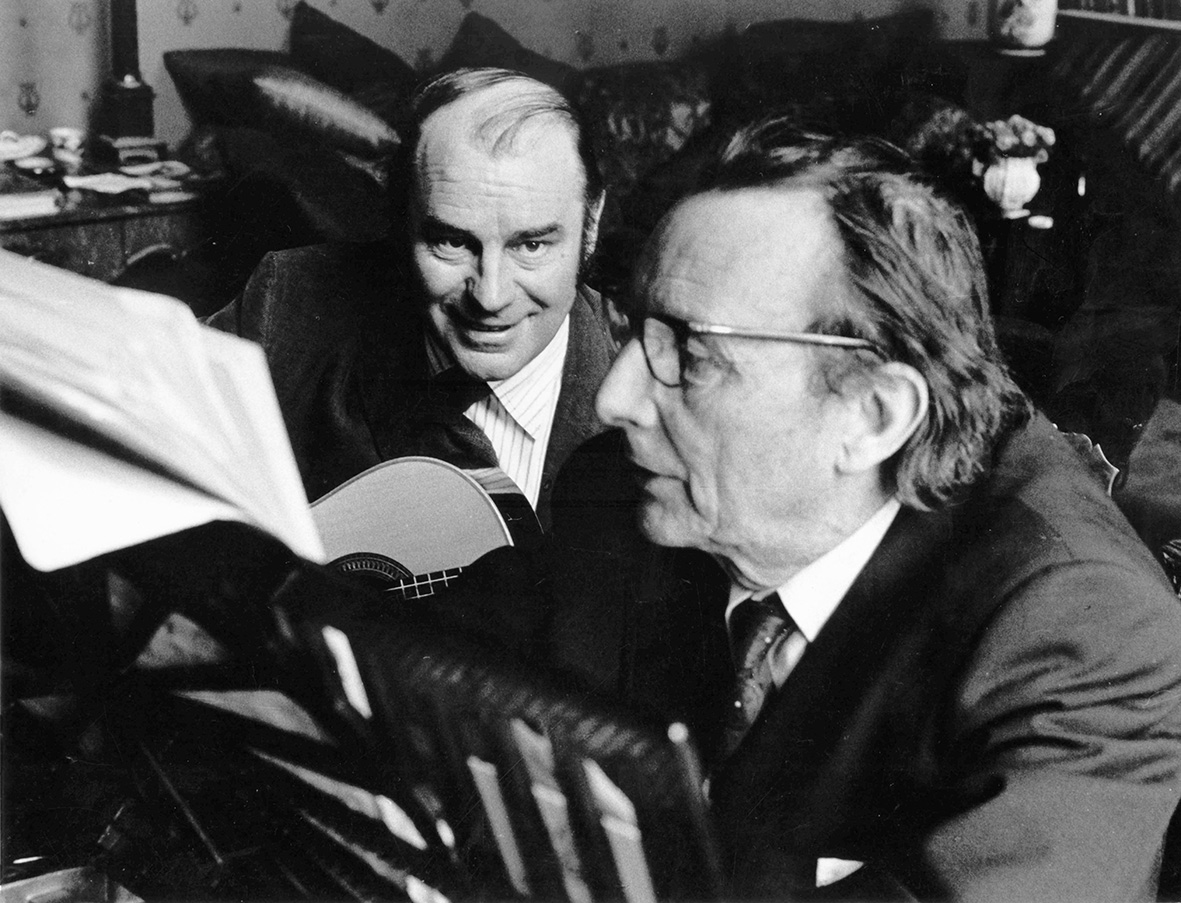

In an email exchange with the author of ‘Lennox & Freda’, American guitarist John Erhardt explains why he likes Berkeley’s music

John Erhardt (3 December 2010):

I wish you could have heard me shout when I saw there was a new biography of Lennox Berkeley. I’m not sure what made me check the Berkeley Society home page yesterday, but I did, and I bought Lennox & Freda pretty much immediately.

I came to Berkeley through classical guitar (I’ve played for 20 years, and currently play his Theme and Variations, plus trois of the Quatre Pièces he wrote for Segovia), and stayed for the symphonies and chamber music. I’m also not a particularly gifted piano player, but I stumble around a few of his Six Preludes, plus a few of the pieces from Opus 4 [Five Short Pieces]. I certainly can’t give complicated musicological reasons for the affinity I have for him, but I’m glad it’s there, even without reason.

You didn’t ask to hear any of this, obviously, but I thought you might like to, only because I’m not sure how often you get non-library orders out of the blue from America, where very few people (even musicians) know who Berkeley is. At any rate, I’m looking forward to reading the book, and I wanted to thank you for writing it. It immediately jumps to the top of my To Read pile.

Tony Scotland (4 December 2010):

Actually I don’t even get library orders out of the blue from America, so your letter, like your order, raised a shout from my side of the Atlantic too. I’m really interested in your feeling for Berkeley’s music. Most musicians who actually get as far as playing it like it too. And of course the precise reasons ought to be irrelevant – that the affinity is there should be enough – but I have to admit to wanting to know why: whether it’s something specifically in the music - the subtle understatement, occasional bittersweetness, the refusal to run with a tune, the leanness of the line, the flashes of wit, the juicy harmonies – or whether the attraction is spiritual. I wonder if my book, which explores the man in intimate detail, and sets him in the context of his faith, his loves, his music and his times, will help your understanding. And I’m so eager for you to find out that I’m going to send the book by airmail so it jumps to the top of your To Read List before Christmas.

JE (8 December):

First off, thanks very much for the expedited shipping – very much appreciated. Second, I apologize for the length of my reply; I have never really tried to get my thoughts down on paper about Berkeley (or music in general) and this sort of spiralled out of control.

I have to mention other composers as I try to talk about what draws me to Berkeley. I’ll start with the guitar-specific reasons, since that’s how I learned about Berkeley to begin with. These are in no particular order.

There’s a technique called tremolo, and it’s quite difficult to do well, and very easy to screw up. If you’re not already familiar with it, you can think of it as a four-note sequence where the right-hand thumb plays a bass note and then three fingers in quick succession play the exact same note. The melody tends to be carried by the bass. This is a video of Julian Bream playing what is probably the most well-known tremolo piece in the guitar rep. [Recuerdos de la Alhambra by Francisco Tárrega].

I don’t particularly care for tremolo. It’s flashy, the ear gets tired of hearing it after a minute or two (or mine does), it tires your hand very quickly, and since it’s so challenging the flashiest tremolo pieces consequently get over-recorded and over-performed. Tremolo also carries an unmistakably Spanish Romantic sound to it. Berkeley used tremolo in the first of the Quatre Pièces, in the final movement of the Sonatina, and the third variation of the Theme and Variations, and managed to remove all Spanish lineage from each piece. You would never, ever confuse those pieces with being Spanish Romantic pieces, and that’s no small feat. So, in a way, he rescued tremolo for me.

Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten once told a terrific story. They had performed a few of Webern’s piano/vocal pieces, and Pears thought them notoriously difficult, even for a professional singer. He admitted he did not get all the notes right – he wasn’t singing what Webern had written, because he simply couldn’t learn the part. After one performance some admirers of Webern came up to him and said that they were deeply moved, and had never heard Webern performed that way. Pears thought, ‘Of course you haven’t – I didn’t really sing what he had written’. As a performer (yes, I’m an amateur, but still), I have a very hard time performing strictly atonal work (true 12-tone work in particular) because it’s the musical equivalent of memorizing three pages of random words that do not form sentences, thoughts, or even fragments. I can accept the possibility that I’m not a good enough musician, though that’s tempered a bit by the professional musicians I know who cannot stand playing 12-tone pieces either. I’ve come to think of music as a sort of Venn diagram consisting of four circles. The first is ‘music you enjoy playing,’ the second is ‘music you enjoy listening to,’ the third is ‘music you enjoy studying’, and the fourth ‘music you enjoy fussing over’. You could probably guess that all my favorite music lies in the overlapping bit in the center of that diagram, but I lose something when only three of the four circles get represented. Berkeley’s in the center of all four.

That doesn’t dismiss atonal music outright, though. Berkeley, rightly in my opinion, used atonal work as a tool, and not the tool. The Theme & Variations switches back and forth between having and not having a tonal center. That’s quite hard to carry off, particularly if you want something lyrical in the end (and the second of the two themes in that piece is extremely lyrical). I’m just into my third decade of playing the guitar, and the Theme & Variations is, without question, the most challenging piece of guitar music I’ve ever studied. It asks more of me as a player than most pieces that were written by a guitarist. Berkeley wasn’t 100% perfect at composing for the guitar (Angelo Gilardino has written about things that Berkeley wrote which were ‘unplayable’ on the guitar and needed to be edited), but he was pretty close. Even the Quatre Pièces, very early pieces that date from his time in Paris, are very mature, demanding pieces.

I’m glad you mentioned the refusal to run with a tune – that is precisely why I love, say, the opening movement of Berkeley’s Symphony No. 1. To start with, you can’t really tell where any of the repeats are. But additionally, there’s so much tension that builds up simply because you get a phrase, and you think ‘that’s really lovely’, and then you realize the music is not readying itself for a repeat of that phrase, even though we’re sort of conditioned to expect that – it’s as if the melody is a racecar and we think it needs to make a second lap around the track, except part of the track is obscured so we don’t know when it’ll make it back around.

I don’t remember offhand who said this, but I do remember it referred to Karol Szymanowski, who I also love (and who I think compares well to Berkeley): ‘Music is not just melody.’ Yes, there’s something great about a hummable tune that you can bring with you as you walk from the theater to your car (I love Dvořák for this reason), but there are also many other things that can be achieved through music, such as tension, or the always-nebulous ‘texture’. Berkeley can write lovely melodies (I defy anyone to listen to the opening of the String Serenade and not hum it within moments), but he doesn’t do that with all of his pieces. So he’s quite capable of writing in a more conservative and romantic idiom, yet he chooses to do something entirely different. Two other favorites of mine do the same thing: Britten and Shostakovich. Their music is more than orchestrating a catchy tune they thought up while in the shower.

I’ll close by saying that the spiritual side of Berkeley interests me a lot, mostly because he ran toward the Catholic Church, whereas I ran screaming from it. But while I am not a religious person, I am interested in religion and spirituality a great deal, particularly in artists. I’m looking forward to what your book says on this front.

I try to evangelize for Berkeley among guitar players, and I have a pretty good success rate at convincing people that this is a composer they should take seriously.

TS (10 December):

Thank you for that wonderful outpouring. Rich and fascinating. Richard Rodney Bennett, who was a student of Berkeley for a while – but the two were never meant for one another – has some amusing things to say in his new biography about LB’s lack of sympathy for 12-tone music. And you’re absolutely right that LB used it, during his brief flirtation with atonality, simply as a tool, a new means of trying to express what he wanted to say. I know your letter was only a letter, but I very much like its tone and the energy of its spontaneity, the feeling of exploring as it goes along. I wonder if you’d allow me to use it, as a Letter, in the Berkeley Society Journal? Our members would be very interested by all that you have to say – about guitar tremolo, atonality and tunes – and it’s extra exciting that it comes from a Berkeley enthusiast in America. Indeed: what about joining? Only a few pounds a year. Do have a look at the website if you haven’t already.

JE (13 December):

Thank you for the kind words. Sure, you’re more than welcome to use the letter. I am curious now that you’ve brought up the Society. I toyed with joining about six months ago but did not do so. I did join just now, though.