Desmond Shawe-Taylor’s correspondence with Lennox Berkeley

Tony Scotland examines letters from Lennox Berkeley to the music critic Desmond Shawe-Taylor

A small bundle of letters written by Berkeley to his friend Desmond Shawe-Taylor, music critic of The Sunday Times, has come to light amongst Freda Berkeley’s papers at her flat in Notting Hill Gate. There are eight letters and one postcard dating from the years 1956 to 1972, together with one letter from Michael Berkeley.

Four years younger than Berkeley, and, like him, an Oxford man, Shawe-Taylor began to contribute musical, literary and film reviews to various London journals, including The New Statesman, from 1933, shortly after he came down from the university. He joined the army early in the war and served in the Royal Artillery till his demob. in 1945. On returning to civilian life he became music critic of The New Statesman and in 1958 he succeeded the legendary Ernest Newman as music critic of The Sunday Times. He died in 1995, at Long Crichel House in Dorset, which he had shared since the war with a succession of cultivated bachelors who formed a sort of literary salon – among them the music critic and novelist Edward Sackville-West, the painters Eardley Knollys and Derek Hill, the ophthalmic surgeon Patrick Trevor-Roper, and the literary and art critic Raymond Mortimer.

Berkeley and Shawe-Taylor first met at Oxford in the late twenties, possibly through Berkeley’s musical godmother Sybil Jackson who lived at Boars Hill, and, as Peter Dickinson records in Lennox Berkeley and Friends, Shawe-Taylor’s writing, in a long career as a critic, ‘showed an especially sensitive response to Berkeley’s new works as they emerged’.1

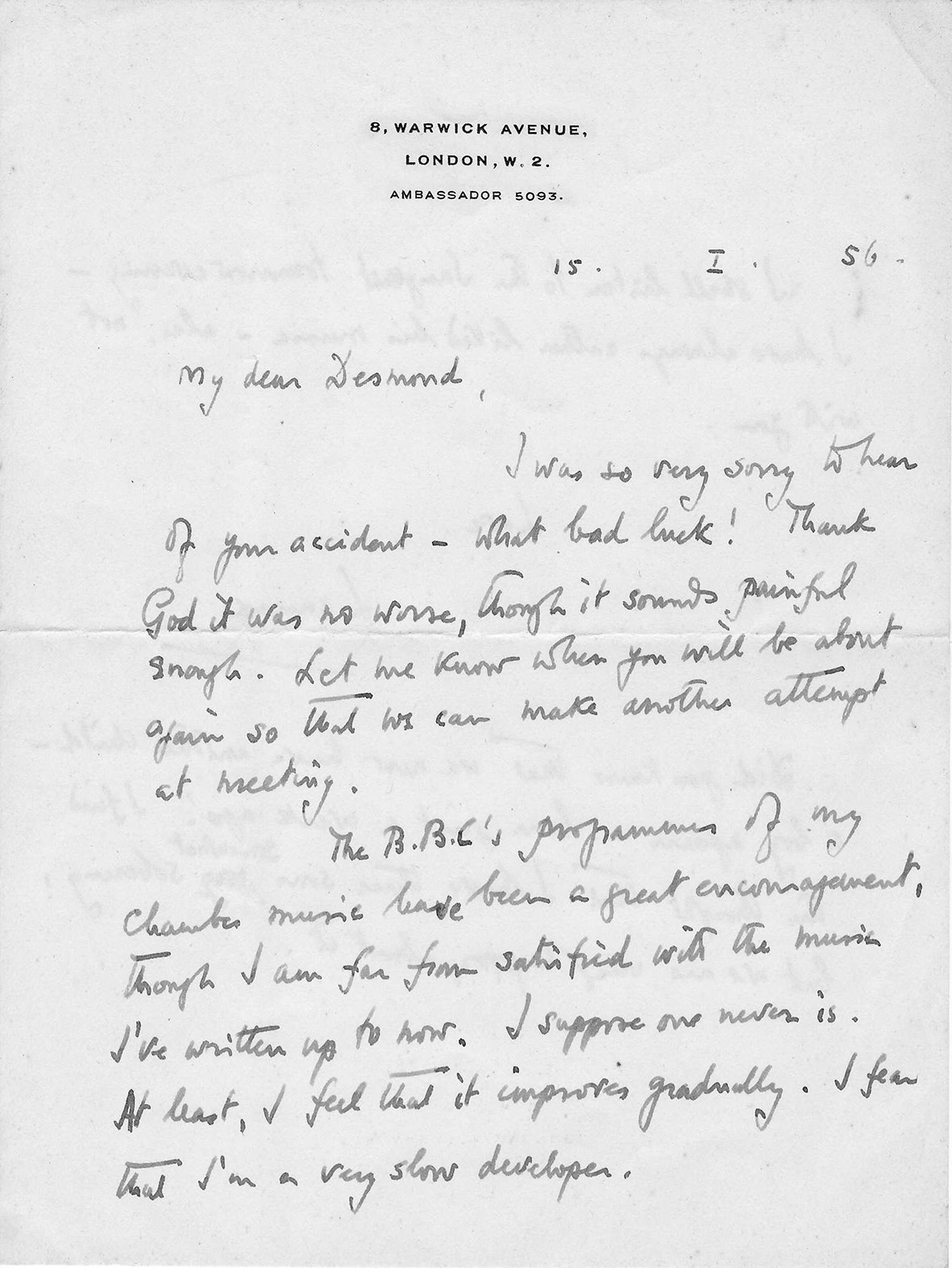

In the first of the letters, dated 15 January 1956, Lennox Berkeley writes to say that the recent series of BBC broadcasts of his chamber music has been a great encouragement, though he adds, with typical modesty, ‘I am far from satisfied with the music I’ve written up to now. I suppose one never is. At least I feel that it improves gradually. I fear that I’m a very slow developer.’

The last letter – from 19 January 1972 – thanks Shawe-Taylor for an article which had appeared in The Sunday Times three days earlier, under the headline, ‘Berkeley’s achievement’:

It’s very gratifying to have some notice taken by the right person! And very useful in encouraging other performances (one hopes). I feel very grateful to you for the trouble you took – this sort of thing gives one courage, very much needed in my case, as I don’t find it gets any easier to write music as I get older – only that one’s actual technique is better – and that is something.

On 19 January 1969 Shawe-Taylor wrote an article in The Sunday Times defending contemporary composers whose work was out of fashion, and the same day Berkeley took up his pen to write to thank him:

I was so greatly delighted by your article [...] it was high time somebody said this, and it needed to be said by a critic of your standing, because it is the critics (with some exceptions) who have been so prone to ‘assess music by the degree of its modernity’. It doesn’t matter so much to composers of my generation, who can at least get our works performed, but it is grossly unfair to young composers who are often denied a hearing because the scores they submit are clearly not in the prevailing fashion. This isn’t the critics’ fault, but indirectly is often due to their influence. So what you say, coming from you, is of great importance and will, I feel sure, do a lot of good. I was glad you mentioned Nicky Maw [Nicholas Maw (1935-2009), a former student of Berkeley at the Royal Academy] who has managed to break through all this, mainly by his very strong musical personality, but also to some extent because he did it just before ‘avant-gardism’ had become obligatory.2

Michael Berkeley’s letter is no less of a tribute to Shawe-Taylor’s courage in speaking his mind. Writing on 20 November 1975, in response to a favourable review of his early Mass and Motet, he says:

Your words were particularly important to me because I know how very much you care about being fair and honest. Not that others are deliberately dishonest, but very few musical journalists seem able either to say what they feel (regardless of fashion) or – if they do – to say it with fresh enthusiasm.

The correspondence also reveals that Lennox Berkeley was asked to write a cello piece for Mstislav Rostropovitch. On Sunday 18 July 1965 Shawe-Taylor invited Berkeley hear Rostropovitch playing the Cello Concerto by Henri Sauguet and the First Cello Concerto by Shostakovitch in a concert with the London Symphony Orchestra in the Royal Festival Hall. Afterwards Berkeley and Shawe-Taylor joined Rostropovitch and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, for dinner with the Harewoods. The following day Berkeley wrote to thank his host:

It was very sweet of you to take me to such an exciting concert – no concert can be anything else if Rostropovitch takes part – and I was delighted to sit next to him – we managed to communicate with a little help from Marion [then Countess of Harewood, later Mrs Jeremy Thorpe].3 Delicious dinner too. I’m very thrilled with the idea of writing something for R and will think about it very seriously. How he can want any more music I can’t think!

Nothing seems to have come of the Rostropovitch idea. The next cello piece that Berkeley wrote was in 1970, for the Prince of Wales. It was the Andantino for cello and piano commissioned by the Performing Right Society for presentation with new pieces by thirteen other composers.

Another of the letters, dated 10 January 1966, shows the extent of Berkeley’s feeling for Mozart – and of the musical education of his sons:

I promised to take Julian [his second son] to The Marriage of Figaro at Sadlers Wells this holidays, and I now find that the only performance before he goes back to school [The Oratory School at Woodcote near Reading] is on Thursday. I don’t like to disappoint him, so I wonder if you’d mind postponing coming to dinner [at 8 Warwick Avenue] to another day if it does not now put you out. I think one must do everything to encourage a real feeling for Mozart at 15!

(It’s a curious coincidence that when Mozart himself was not far off his 15th birthday in 1770 Lennox Berkeley’s great-great-great grandfather, Kenneth, Viscount Fortrose, an accomplished harpsichordist, encouraged his own ‘real feeling for Mozart’ by inviting the young Wolfgang and his father Leopold to make music with him at home in his apartments in Naples.4)

The 1956 letter also records the birth of Lennox and Freda Berkeley’s son Nicholas Eadnoth, with the comment, ‘I find the thought that I have three sons somewhat sobering, but we are very happy about it.’

These nine letters will eventually join the rest of the Berkeley Family Papers on loan at the Britten-Pears Library in Aldeburgh.