Lennox Berkeley Friend and Teacher

The composer and music administrator Sir John Manduell, founder President of the Lennox Berkeley Society, recalls a long friendship with his old teacher, Lennox Berkeley

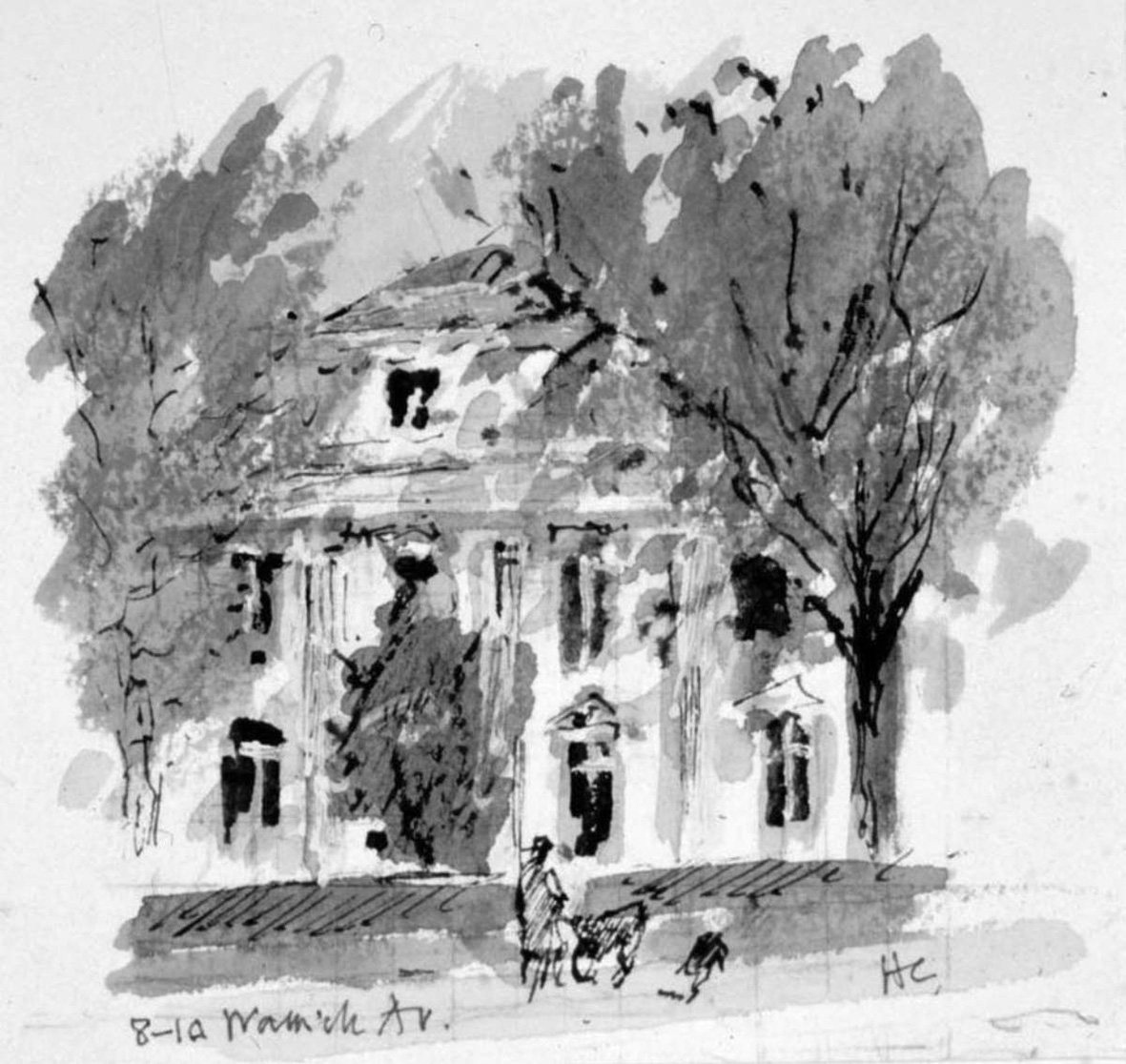

The successful acquisition of the green plaque on the wall of 8 Warwick Avenue has naturally given much pleasure and satisfaction to friends of Lennox. Henceforth, visitors to London’s Little Venice can all be reminded that one of this country’s most admired and distinctive composers lived for a long time in that fine house. Thinking about this welcome development also prompted for me a small clutch of personal memories.

For the first of these the date is April 1955 and I am hesitantly, indeed very nervously, walking up the short front path towards Number 8 for my very first lesson with Lennox. Not only was I intensely nervous, which, as it turned out I had no reason to be, for Lennox was ever the most gentle of men, but until only a few weeks earlier I could have had no idea that I would shortly be studying with Lennox. This was simply because, having arrived at the Royal Academy of Music from South Africa the previous September to take up a PRS Composition Scholarship previously held by John Joubert, I had been assigned to study with William Alwyn. However, half way through that spring term, Alwyn had abruptly left the Academy when he failed to be appointed its new Principal. Myers (‘Bill’) Foggin, who was then the R.A.M.’s Warden and who was shortly to become Principal of Trinity College of Music, very courteously consulted me about an alternative tutor, whereupon I naturally had no hesitation in asking if I could be included in Lennox’s class. In this way, and to my intense delight, I was given the chance to study with somebody whose music I had long admired whilst still at home in South Africa. So it was that on that cold April morning I found myself knocking on that big blue front door.

My second memory sees Lennox himself receding up that same footpath to Number 8. It was the following autumn, and in circumstances on which I still look back with at least mild amusement, if not some amazement. Improbable as this may now seem, one could still, in those far-off days, park cars on the flagstone area in front of the R.A.M. I was the proud possessor of a very old and very suspect green Vauxhall 14 whose wings and running board were largely held together by faith and sellotape, in ways which were still possible in those pre-MOT times. By chance I was leaving the Academy at the same time as Lennox was making his own way out. On an impulse I asked him if I could give him a lift home. To my delight he unhesitatingly accepted the suggestion and there we were, a few minutes later, bowling westwards along Marylebone Road prior to arriving safely at Warwick Avenue. To this day I marvel that dear trusting Lennox should have delivered himself up to a young unproven driver and such a highly dubious vehicle. As I watched him making his way up that same garden path, I experienced a certain youthful exultation at having had the opportunity to drive somebody who already, at that time, occupied a position in my mind of near divine pre-eminence.

My third memory of the path to No 8 follows a year or two later. I had begun my time at the BBC as a young Music Producer, and on the day in question I had been in one of the BBC’s Maida Vale studios, in nearby Delaware Road, recording a guitar recital by Julian Bream. In those days it was still customary for the announcer to record introductions on the spot. Alvar Lidell, that widely-admired and most musical announcer, was bringing to the proceedings his own inimitable brand of authority. As was customary, he had been provided with notes prepared by Deryck Cooke’s Music Presentation Unit and on this occasion by a Hungarian lady, Magda Benda, who was always a stickler for precise accuracy. However, when Alvar pronounced that the next work’s authenticity might be questioned, but that it was thought to be by Bach, Julian Bream spontaneously interrupted in his characteristically direct manner: ‘What do you mean, Alvar? Who says “thought to be by Bach”? It’s so bloody good it must be by Bach.’

When that lively session was over, and Julian and I were wandering up to catch the tube at Warwick Avenue station, I asked him if he knew Lennox, or would like to meet him. Unhesitatingly, Julian agreed, and a few minutes later, there we were walking up the path to knock on that fine blue door prior to what I believe was Julian’s first meeting with Lennox. When we think about the Guitar Sonatina, the Theme and Variations and the Concerto which were to follow, I believe it is natural to look back upon that first improvised meeting as one which was to carry no small significance for Lennox.