Berkeley as mentor – and inspiration

Sally Beamish recalls the profound encouragement which gave her the confidence to become a composer

It was in 1973 that a friend of mine, the violinist Ruth Crouch, introduced me to her friend Jonathan Rutherford, who was a pupil at the Menuhin School. I was sixteen, and a keen composer, but had received no formal tuition apart from being prepared for Grade 5 Theory by the composer Brian Chappell when I was ten.

Jonathan was studying piano, but his main interest was composition. As there was no composition teacher at the school, his mother had organized lessons for him with Lennox Berkeley. I was hugely impressed. I knew Berkeley’s music through my violinist mother (Ursula Snow), who had recently performed his string trio, and had visited him in Warwick Avenue to play it through to him. (I remember she remarked that he was very complimentary, and didn’t give them the detailed analytical coaching session they’d been hoping for!) I had also performed his viola sonata, and accompanied a friend who had played the recorder sonata in a diploma exam.

Jonathan offered to take me along to meet Lennox one afternoon in the autumn of 1973. Jonathan had written a children’s opera based on Wilde’s The Nightingale and the Rose, and he played it through on the piano, singing the vocal lines where he could. I was drafted in to play some of the upper lines. I then showed Lennox a short piano piece I’d written, and he was very encouraging. I seem to remember most of the afternoon was spent chatting, rather than in any kind of formal teacher-student relationship. I was overwhelmed and nervous, and felt an impostor.

To my delight, Lennox invited me to visit again, and a few weeks later, at a concert, someone asked me who my composition teacher was. On an impulse, I said ‘Lennox Berkeley’, and then had several sleepless nights worrying that this was not really true, and that I might somehow be ‘found out’.

I visited Warwick Avenue several times before going to the RNCM in 1974 to study viola. The family were always friendly and welcoming, and I became very fond of Freda. At the RNCM, I was delighted to discover that John Manduell, the then Principal, had engaged Lennox as visiting lecturer. Although I was not on the composition course, John made sure that I was always included in the class when Lennox came to visit.

When I look back on these ‘lessons’, I honestly can’t remember any nuggets of wisdom, or instructions, or critical judgment of my work. All I remember is that, through Lennox’s encouragement, I gradually came to think of myself as a composer. He talked to me as if we were ‘in it together’ – as if what I had to say was just as valid as what he had to say.

I do remember him telling me he didn’t understand how music could be atonal. Of course, I experimented with serial technique, and once I showed him a violin sonata in which I written a passacaglia using all 12 notes, but firmly within A minor. This he approved of.

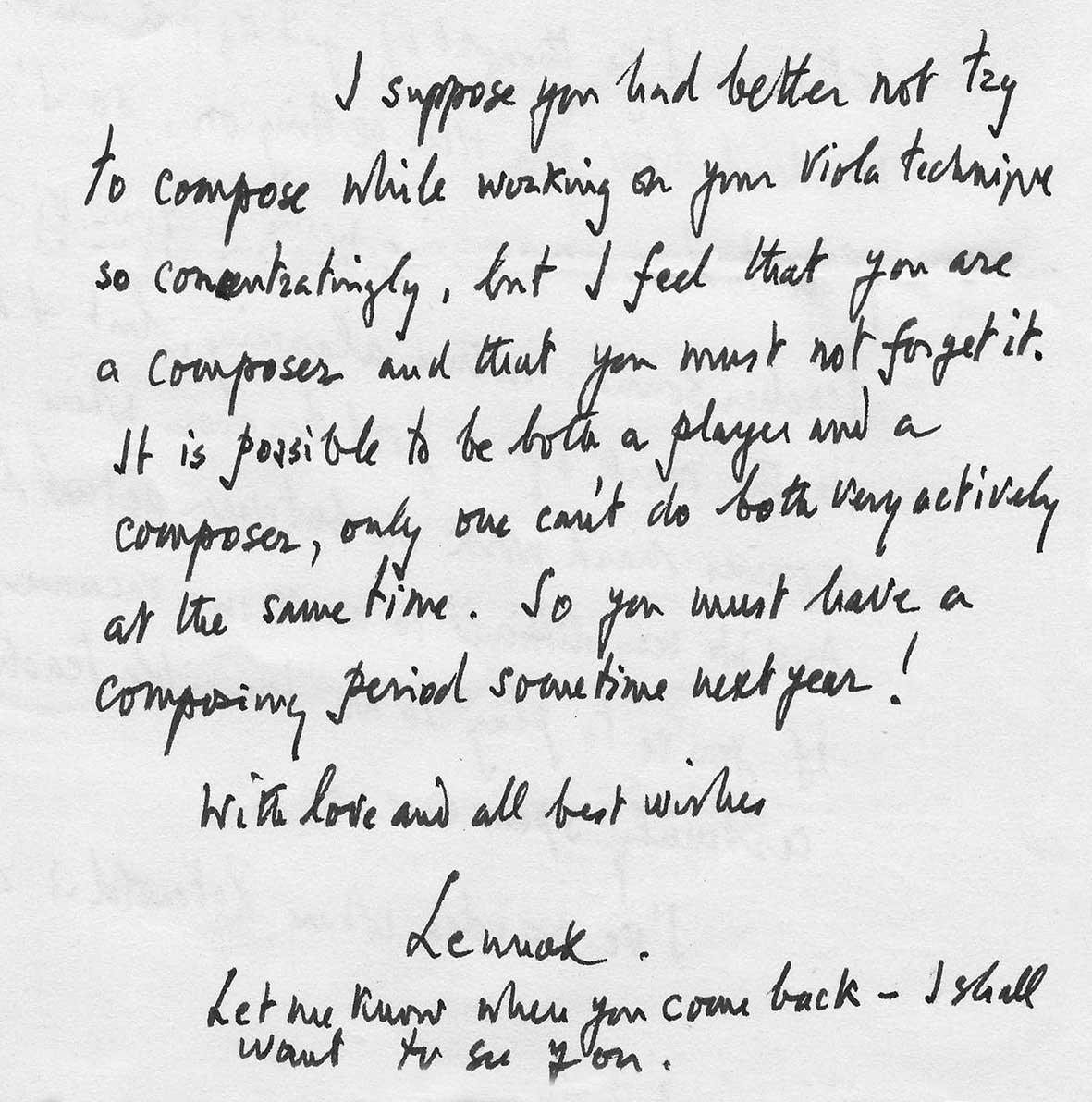

In 1979 I went to Germany to study the viola. Lennox was concerned that I might be losing touch with composition, and wrote a letter which had a profound effect on me. In it he said, ‘I suppose you had better not try to compose while working on your viola technique so concentratingly [sic], but I feel that you are a composer and that you must not forget it’. The impact of his faith in me, on my confidence and motivation, is hard to quantify, but I feel that without it, I might never have had the courage, finally, in 1990, to make the break from the viola and become a full-time composer.

In 1985 John Manduell invited me to be one of the 14 composers to contribute a variation on a theme from Ruth as part of Bouquet for Lennox to celebrate his 75th birthday. This gave me my first experience of writing for orchestra, and it was performed by the Philharmonia at the Cheltenham Festival. This was unimaginably exciting. I crept in, uninvited, to the London rehearsal on the day before, and I remember the conductor, Brian Priestman, saying ‘Hold on to your hats’ when he got to my Variation 3: I didn’t realize that what I had written was tricky. I was quite chuffed that my variation lasted exactly one minute – the time prescribed.

My last meeting with Lennox was just before I moved to Scotland, in 1990. He was already lost in dementia, and couldn’t really converse. Freda asked me to play Beethoven sonatas to him on the grand piano in their living room. I will never forget the delight and recognition on his face as the music broke through the tangle in his mind. It was an expression of utter peacefulness.

Freda and I discussed my impending move and career change, and suddenly, Lennox said quite clearly ‘You must be careful taking yourself away from the centre’. I explained the reasons for my move to Scotland, but he had nothing more to say, and retreated into his own world. That was the last time he spoke to me.

I wish I could now tell him how Scotland turned out to be the beginning of a new world of opportunity for me. I would love him to know how much those early conversations meant to me, and how the warmth of the Berkeley household became a very special part of my life.