‘The music of loss’ in the poetry of A. E. Housman

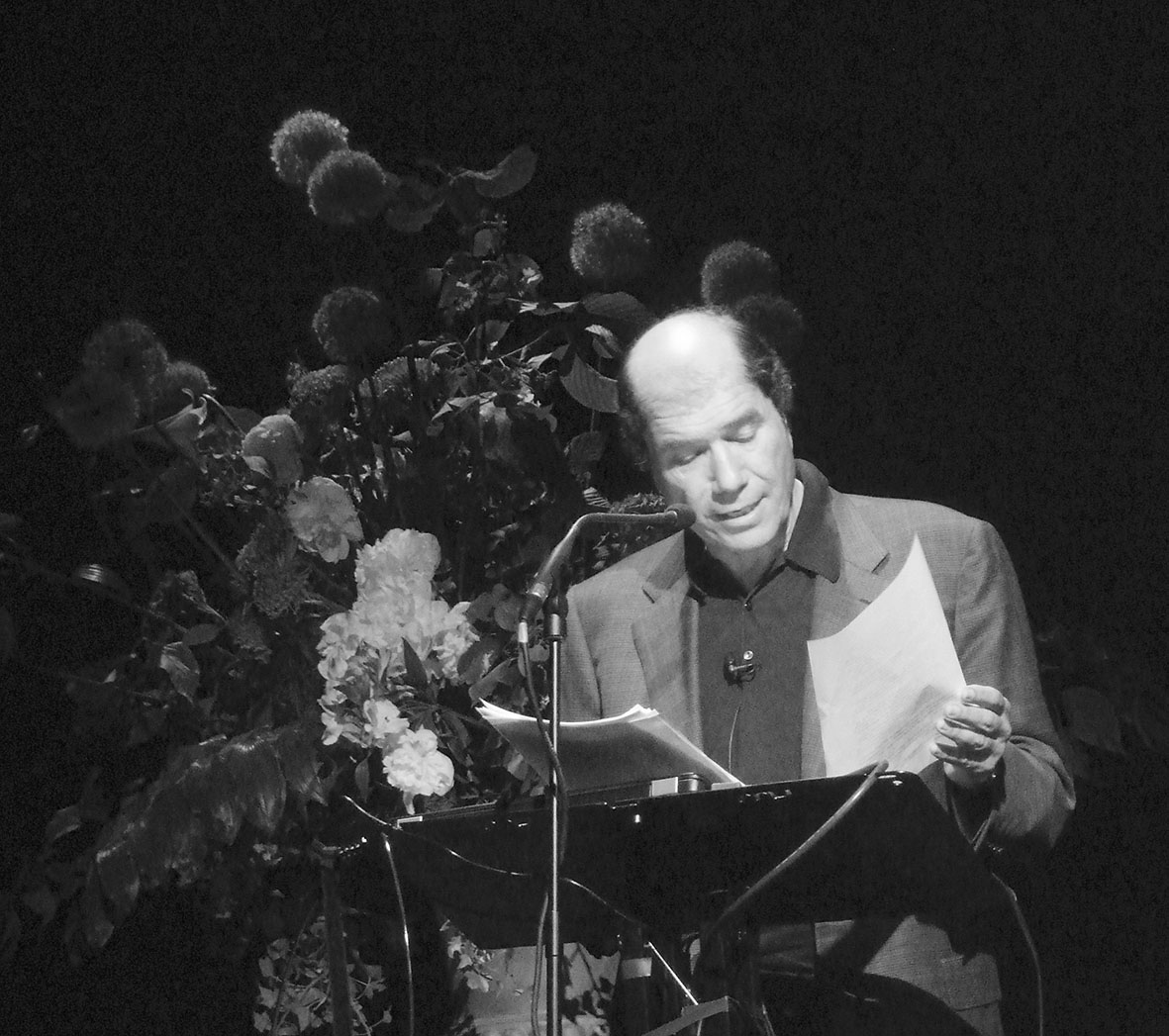

The composer Michael Berkeley describes how Housman’s poetry inspired Lennox’s work

Unlike Housman I am not a classical scholar and so my talk will concentrate largely on the emotional motivation of poetry and music (especially as seen through my father, Lennox Berkeley, who was, in many ways, a Housman-like character).

Humans need to yearn. We need to seek the unattainable. Therefore, in some ways, we are doomed, for if what we seek is unattainable we can never be truly satisfied. Animals do not have this problem since they do rather than think about doing. Humans discuss and engage in endless prevarication, justification, fear and, let us not forget our prize plum, guilt. Many find in religion some answer to the eternal quest to understand why we are here. Others turn to music and poetry.

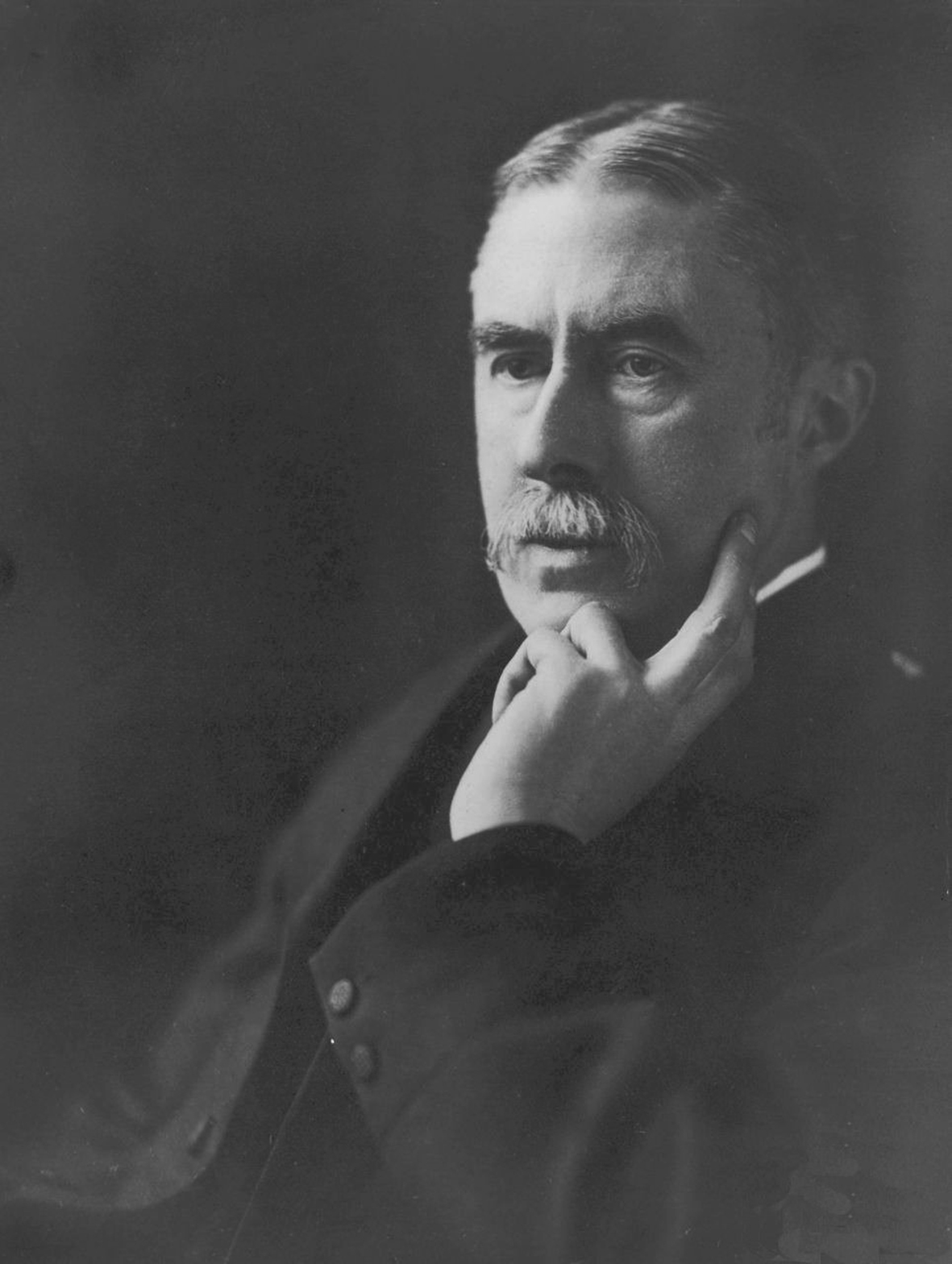

At first sight, Housman’s quiet but ferocious intellect seems at odds with his emotional, even naive, yearning: a male friendship and unrequited love. Rather than re-recite Housman’s probable homosexual love for his definitely heterosexual Oxford friend Moses Jackson, I would like to consider whether this was not precisely the catalyst Housman required to ignite his poetry and whether, had it not been Moses, it might just as easily have been Jack Sprat. In other words do artists require emotional turmoil to fuel their creative engine?

In Housman we see, initially, an unusual marriage of classical Latin scholar par excellence and the kind of hopeless would-be-lover of the sort the Greeks rather despaired of. They invented the word mania to cover just this sort of obsession. It is a mark of the wonderful madness of the human condition that intellect and emotion can be, perhaps need to be, so exhilaratingly in conflict; productively so, for the poetry of Housman uses classical skeletons to structure and support the romantic flesh.

Yet music is able to blur the edges: in its pure abstraction it is less specific than words or visual images – it leaves the listener to decide what it means. As a composer I am always more immediately receptive to ideas when I am setting a text, rather than facing a blank sheet of paper, because a poem or libretto or even a picture immediately conjures up, if not always a precise musical idea, certainly a sensibility. Words anchor us where music leaves us adrift, floating free.

I recently discovered a great deal more about my father’s relationship with Benjamin Britten through a penetrating study by Tony Scotland [Lennox & Freda, Michael Russell Publishing, 2010]. It is the story of how an ostensibly gay man changed his emotional centre of gravity and fathered a happy family, and how that affected his music. The parallels with Housman are striking, if, of course, different. Housman suffered from a lack rather than a loss – and the two are worlds apart. Lennox was in love with Ben’s gifts as much as with the man himself, and when he lost the man to Peter Pears his most eloquent description of his feelings came in two of his finest songs, both settings of Housman. One is:

‘Because I liked you better Than suits a man to say, It irked you, and I promised To throw the thought away’.

The other:

‘He would not stay for me, and who can wonder? He would not stay for me to stand and gaze. I shook his hand, and tore my heart in sunder, And went with half my life about my ways.’

There is an obvious connection between Berkeley and Housman, not just in the sentiments of the poems but also in the fact that my father, like Housman, was spiritually a neo-classicist, yet in the presence of words – both sacred and secular – a romantic element is allowed to blossom.

Though Lennox – and Britten – set Auden, only Lennox set Housman. The composer Ian Venables has rightly suggested that the simple folk-like verse of Housman is in fact a trap for the composer – that the internal complexities and, in particular, the irony make the lines far harder to set than it seems at first. This is why, he suggests, that certain composers, most notably Britten, have avoided Housman – even though his poetry has been set to music almost more than any other verse in the English language. I am not sure that I entirely agree with Ian about this. I think my father’s Housman settings get to the very essence of the poetry, and I would like to think that in my own setting of Grenadier (commissioned by the Housman Society), the apparently straightforward and lyrical setting is in fact subverted by the music gradually or suddenly slipping or diving into something surprisingly frenetic or angry.

Britten was probably the finest setter of words since Purcell (whom he studied and performed) and his choice of texts was helped by well-read friends like Peter Pears and, in the case of French literature (and, particularly, Les Illuminations), my father. In Lennox & Freda I learned a lot more about how poetry helped form my father’s aesthetic sensibility, and some of this, naturally, rubbed off on me.

All four of Lennox’s Housman poems are about parting, all are bleak and final. The first is about the pain of unrequited love, and the second about a young soldier marching off to war; the fourth seems to suggest that the loved one is in love with himself, so he must avoid his lover’s eye or see his own face and, like his lover, die. Lennox started his Housman songs just after Britten had gone to America with Pears, and completed the first four in January 1940, but later in the year, by which time he had met a new friend, he added that fifth song, ‘Because I liked you better’.

Britten’s choice of texts, in which innocence is corrupted, reveals the turbulence of coming to terms with his own psycho-sexuality; he was able to impart this both with and without words. In mirroring the sudden changes of mood of the sea, in Peter Grimes and Billy Budd, Britten was mirroring, I have often thought, his own troubled waters in a not totally un-Housman-like manner. Where Housman had an unerring literary technique, Britten had the musical equivalent, and both men possessed an unfailing ear.

If Housman’s yearning was indeed based more on lack than loss, he did experience real loss when his youngest brother, Herbert, was killed in the Boer War. In Grenadier he writes with a savage irony about the boy who goes to war:

‘The Queen she sent to look for me, The sergeant he did say, Young man, a soldier will you be For thirteen pence a day?’ … ‘My mouth is dry, my shirt is wet, My blood runs all away, So now I shall not die in debt For thirteen pence a day.’

My own setting of that poem uses a disarmingly simple folk-like melody (albeit with a bitter and violent twist) to make the shattering awfulness of the waste even more telling.

The Australian writer David Malouf poses eloquently the question I have been attempting to answer:

How is it, when the chief sources of human unhappiness, of misery and wretchedness, have largely been removed from our lives … that happiness still eludes so many of us? … What is it in us, or in the world we have created, that continues to hold us back?’

To which I can only say that we live and love to yearn, and that more is less – that instant gratification is ultimately soul-destroying, and that the muscles of the mind atrophy if not worked, and worked hard. Housman was a good example of that.