‘A Dinner Engagement’ and ‘The Bear’ at the Royal Academy of Music

As an introduction to the student production of Berkeley’s comic opera ‘A Dinner Engagement’ and Walton’s extravaganza ‘The Bear’ at the Royal Academy of Music, Michael Berkeley discusses the two composers, and recalls their light-hearted friendship

Why is William Walton’s Façade an important twentieth-century creation? Though there had been examples of Sprechgesang and Sprechstimme – vocal techniques between singing and speaking – in the expressionist Austro-German music of Vienna (most notably in Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire of 1912), the idea of a narrator (or narrators) reciting poetry to an instrumental accompaniment was novel in British music. Then there is the fact that this nonsense, almost Dadaist, verse by Edith Sitwell is, in its own right, highly original and strangely telling. But what’s more important, to my mind, is that the Sitwell poems drew from Walton music and orchestration that were utterly fresh, entertaining and beguiling.

It is not an easy work to pull off (I speak as one who has both conducted and narrated it), and the rhythms and balance, in a score requiring trumpet, saxophone and percussion in a small chamber group, present extremely tricky problems to solve.

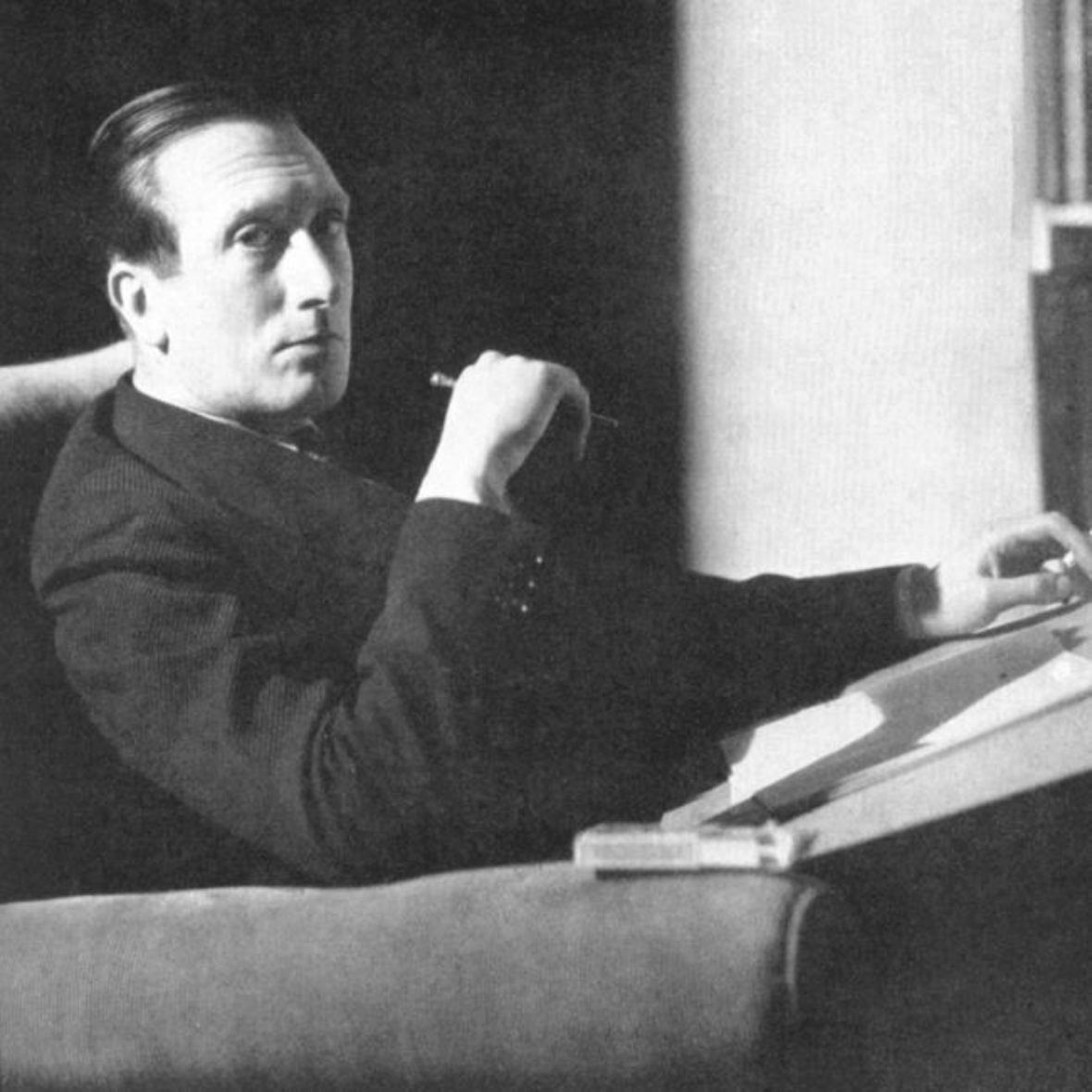

Walton himself was mild-mannered but could be acerbic, waspish. He had a dry and wicked sense of humour (which doubtless attracted him to Chekhov’s The Bear as an operatic subject), and a strange insecurity even about his most successful works – unlike Lennox who knew his worth exactly, was happy with that and never overstated it. Lennox and Freda used to visit the Waltons at their remarkable house and garden on the island of Ischia, and William and his formidable Argentine wife Susana (who would have made a fine Grand Duchess in A Dinner Engagement, though she was somewhat average when narrating Façade) were regular guests at my parents’ house in Little Venice. On one such evening, when, by chance, I had just performed Façade as a student at the Royal Academy of Music, I asked William if he would sign my score and he inscribed most humbly, ‘To Michael, who I hope enjoyed it’.

Lennox certainly loved the winning silliness of the words of Façade, in numbers like ‘See me dance the Polka’, the brilliance of the lyricism, the snappy rhythms, and I particularly remember him pointing out to me how the fusion of text and musical ideas was further enhanced by the brilliance of the instrumentation. In terms of musical aesthetics, though, Lennox was the antithesis of Walton. Where William would hit home with military marches and music of high drama, and could milk an emotional high point, Lennox was more reserved, required more studious listening and prized craftsmanship – French polish. But both composers not only shared admiration for each other’s work but also a mischievous sense of humour, and it’s there in the music of both.

William was a terrible pianist and Lennox had a hopeless singing voice, so when their operas, The Bear and Castaway, were premiered in a double bill at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1967, they both liked to quip that the worst musical experience imaginable would have been been a read-through with Willie playing and Lennox singing. I remember them delighting in, and playing around with, Paul Dehn’s naughty and ludicrously ‘foreignised’ lyrics for The Bear: ‘Madame-er, je vous prie-er, will you make love with me-er’.

Comic opera is very hard to pull off, and it is perhaps remarkable that both The Bear and A Dinner Engagement should have fared far better that the more serious operas of Walton and Berkeley. Indeed they are two of the most successful and performed of 20th Century British operas and make an engaging coupling; the raucous Bear rearing up and belching all over the refined niceties of the genteel guests at A Dinner Engagement.

Walton was a North Country boy who won a place at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1918 when he was only sixteen, but two years later he was sent down for neglecting his non-musical studies. Taken up by Edith Sitwell he was invited to London, where he was fêted and seduced by a glittering and privileged set that must have been as fascinating as it was strange to this gifted young composer from Oldham. But he revelled in the somewhat outrageous brave new world in which he soon found himself (quite literally) housed: for the Sitwells offered him a home in the attic of their house in Chelsea (where, as he used to say later, ‘I went for a few weeks and stayed about fifteen years’).

Façade - An Entertainment arrived as something totally new at its first outing in 1923. The premiere was a succès de scandale, with the eccentric-looking Edith Sitwell declaiming her verses from behind a painted curtain through which her megaphone protruded. The proceedings were roundly condemned in the press: ‘Drivel they paid to hear’ (Daily Express), ‘relentless cacophony’ (Manchester Guardian). The clarinettist asked the composer what his brethren had ever done to him to deserve such a difficult part, and Noel Coward stomped out of the first public performance in the Aeolian Hall in 1923. Walton, however, had made his mark, and before long Façade became an accepted, if unusual, classic, both in its original chamber form and in its re-birth as an orchestral suite. Frederick Ashton created a ballet on it and numbers like Popular Song were used as television theme tunes.

Walton’s flame burned brightly for the next couple of decades, with works like the febrile and driven First Symphony, the lyrical and melancholy Viola Concerto, the Violin Concerto and Belshazzar’s Feast securing him a frontline reputation. His gifts rather faded thereafter, and nothing he wrote in later years quite lived up to the emotional strength of those early and white-hot works (he always regretted that the Second Symphony and his opera Troilus and Cressida were not better regarded), or the flash of uninhibited youth and naughtiness that combined to create the extraordinary Façade.

It is a work, I think, that can be enjoyed on many levels – as pure fun; as something completely new in concept; as a remarkably skilful piece of instrumental craft and melodic and rhythmic ingenuity; or as an experience that you do not attempt to analyse in any of these ways but simply sit back and experience as a foretaste of the ‘happenings’ of half a century later. Whichever, you will never be bored!

Many of these qualities are to be found in abundance in A Dinner Engagement (brilliant scoring and effortless lyricism) and The Bear (joie de vivre and melodic ebullience), and it will be delicious to sample these two operatic dishes.