Theme & Variations for Guitar

Swedish/Greek guitarist Ioannis Theodoridis analyses Berkeley’s ‘Theme & Variations for Guitar’ – and finds traces of Beethoven

Lennox Berkeley’s Op. 77 enchanted me within seconds of hearing it. The idiosyncratic but promising gesture that unfolds the main theme immediately sparked a genuine curiosity and excitement. Because of its richness and many challenges, it proved to be an excellent work to immerse myself in, which lent itself to this B. Mus. dissertation at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm.

The purpose of this project was to provide myself with the best possible conditions to interpret and portray this magnificent and mysterious piece for future performances. Besides the technical difficulties, the form of theme-and-variations especially forces the musician to confront an array of analytical challenges. Therefore, I decided to focus this analysis mainly on thematic and structural patterns to present the reader with a clear, and hopefully objective, main overview of the piece.

Published information on this Theme and Variations is scarce, to say the least. Since Berkeley wrote a great deal of excellent music, this relatively small piece for the guitar doesn’t stand out enough to be mentioned much, if at all, in the available books about him. Even when the guitar pieces are noticed, attention focuses on the larger works, such as the Sonatina Op. 52 or the Guitar Concerto Op. 88.

It became clear that the closest living source was the guitarist who commissioned the work in 1970, Signor Angelo Gilardino himself. However, it never struck me to dare ask for an interview until in early April 2014, when by chance I renewed a brief acquaintance with the great Swedish guitarist Magnus Andersson, a pupil of Gilardino, whilst visiting the Music and Theatre Library in Stockholm. I had met Magnus a year earlier when he had given a few lectures at my college, so we started talking, and when I mentioned the paper I was researching, he explained how the commission had come about. Magnus convinced me that I should contact Gilardino; furthermore he kindly offered me a personal introduction – and promised ‘a lovely response’. And indeed Signor Gilardino’s reply was wonderfully helpful:

I wrote a letter to Sir Lennox with some comments about his previous guitar work, Sonatina, and he kindly replied. Then, I felt encouraged to introduce my purpose of enlarging the guitar repertoire with the powerful support of the Italian publisher [Bèrben] which had created a new collection of original 20th century guitar music and which had entrusted me with the editorial care of that series. With such a credit, I asked composers to write something new for the instrument, and I asked Sir Lennox also. He was extremely polite to me, and within a short term, one month or even less, he sent me the manuscript of the Theme and Variations. It was written with such skill, both from a compositional viewpoint and for the use of the idiomatic resources of the guitar, that I felt it should have been published exactly as it was written, with only one or two footnotes. My editorial intervention upon the piece was restrained to the addition of fingering only. Later on, in 1974, I sent Sir Lennox a copy of an LP I had recorded, including his piece, and once again he answered with his kind and appreciative comment. It was one of the easiest, finest and more instructive experiences I ever enjoyed as a musician.

According to the Berkeley source book,1 the piece was written and finalised by 1 September 1970. Apart from that there isn’t much more information available. Luckily, there is one interesting quotation by the composer himself, in his diary entry for 20 January 1973, when he assesses Julian Bream’s performance and interpretation of the piece:

Julian Bream came to play me my Theme and Variations … we went to his recital the next day at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. He’s without any doubt a great musician who adds to his purely musical talent and fabulous technique a superb sense of performance. His playing of my piece was as nearly perfect as I could imagine, and this indeed was true of the whole recital.2

For me the most telling introduction to this work is found in the Handbook of Guitar and Lute Composers, which describes Berkeley’s compositional style as ‘instrumental without worn clichés’, and it goes on:

Theme and Variations (1970) for the solo guitar has, thanks to its naturally idiomatic understanding of the guitar, reached a secure position in the guitar repertoire. Due to its technical difficulty this excellent piece is suitable to be played at an early stage of professional guitar studies.3

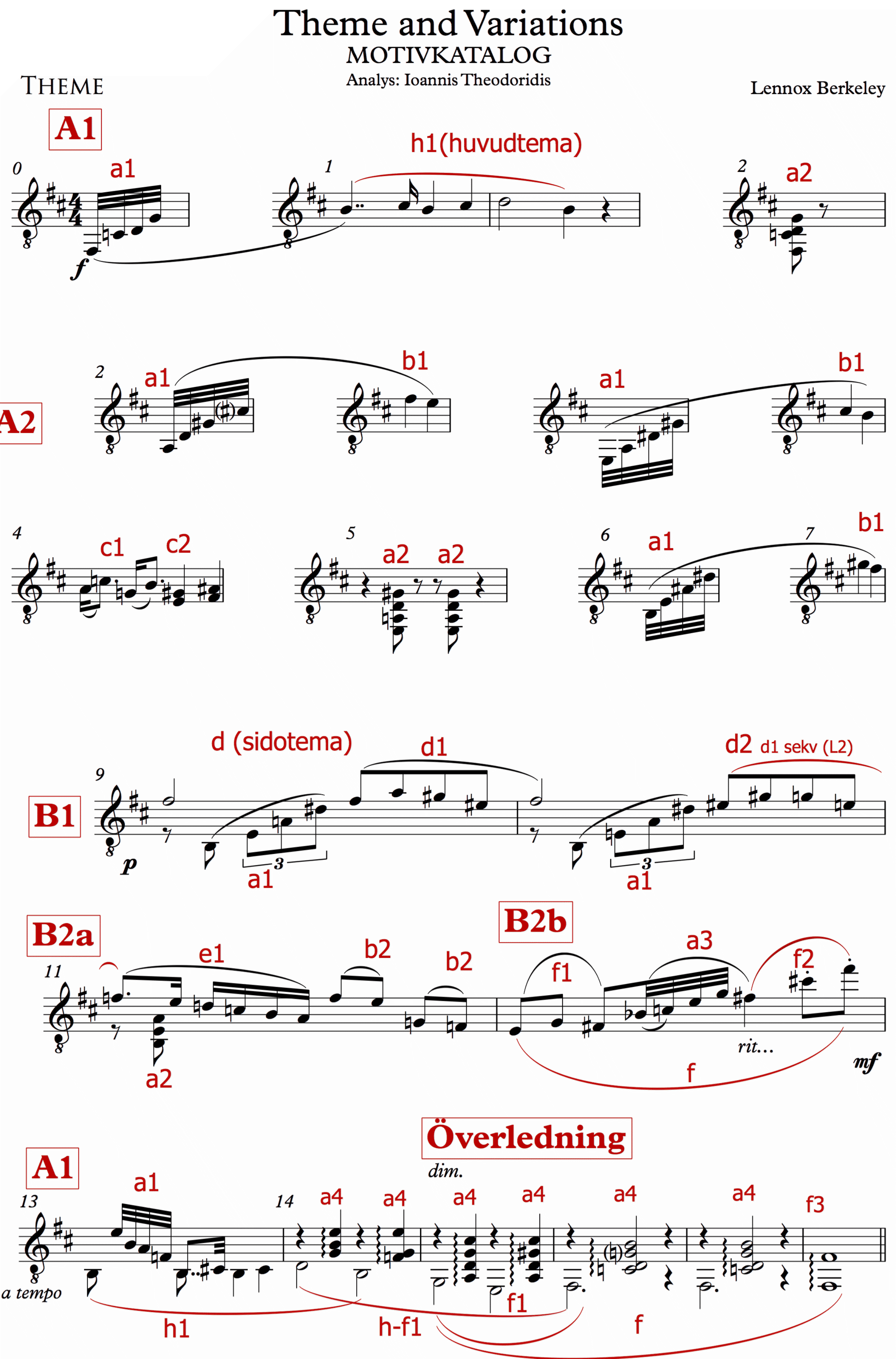

My analysis begins with a ‘Motif catalogue’, edited by separating the bars from the original ‘Theme’. (To clarify the terminology: the motifs are identified with lowercase letters, and form sections with uppercase letters in the style of rehearsal marks. The reason for not naming the main theme ‘b1’, and calling it ‘h1’ instead, is to distinguish it from the ‘A’ and ‘B’ form. The analysis was originally done in Swedish, so the letter ‘h’ abbreviates the word huvudtema or ‘main theme’. The second most important theme is the theme named ‘d’ that I had planned to name ‘s’ to mean sidotema or ‘secondary theme’. However, ‘h1’ remained the only irregular exception).

Perhaps the most characteristic part of the opening of this piece is the way the lyrical melody of the main theme (h) clearly contrasts with the rougher motifs (a1 & a2) below; motifs that create an almost sinister sound while they lurk below the melody. The main phrases in the A and B sections are the ideas that can be most clearly heard in the succeeding variations. The Theme is in simple ABA form followed by a coda/modulation. The Variations reflect a similar order, but all of them exclude the clear recapitulation except for Variation II.

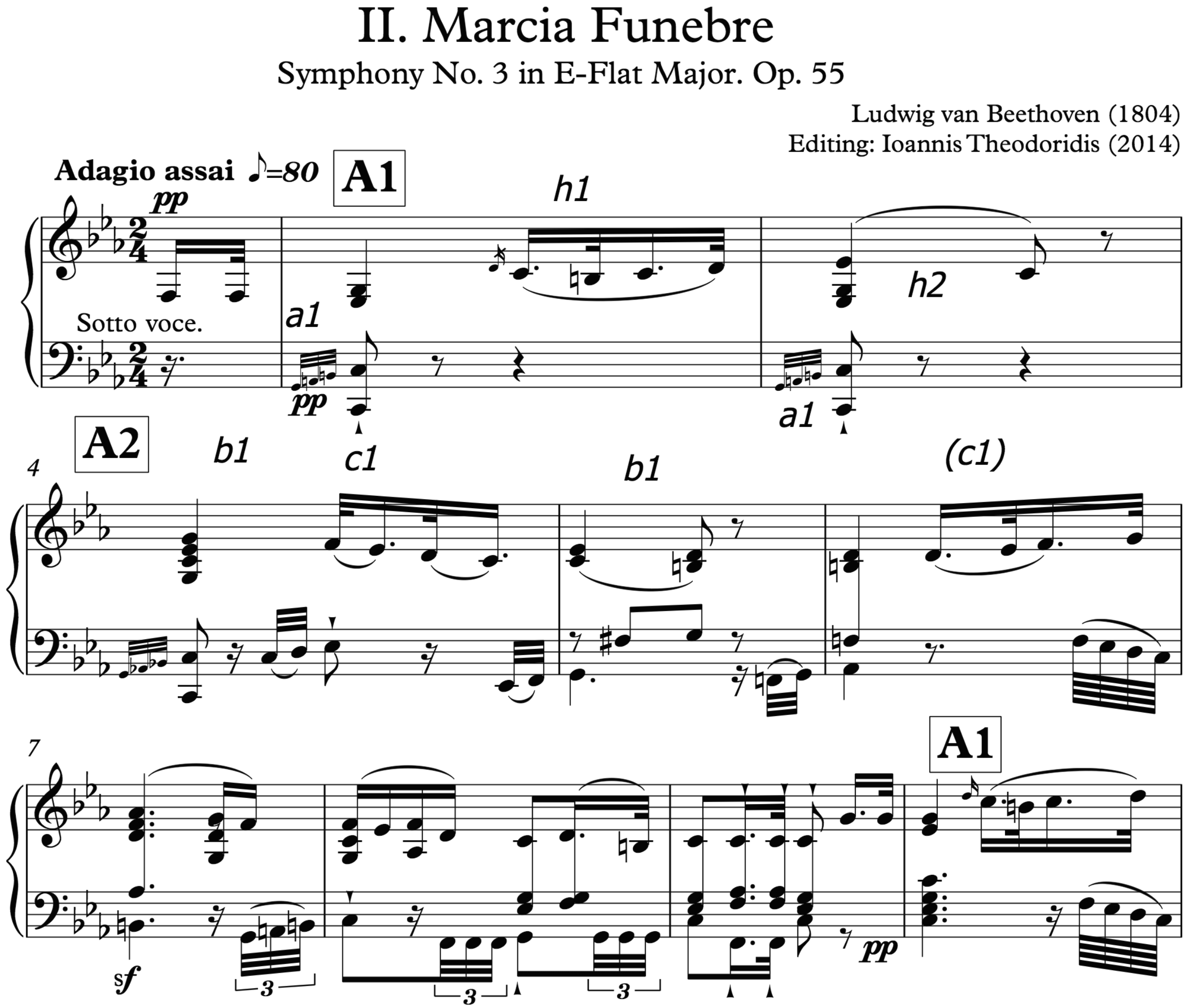

My tutor at the Stockholm Royal College of Music, Peter Berlind Carlson, alerted me to the possibility that Berkeley’s ‘Theme’ seems to quote from the ‘Adagio’ movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. Three, the ‘Eroica’. The guitarist Eric Lammers was even more convinced: he told me that after one of his performances of the Berkeley Theme & Variations, a violinist had come up to him and remarked on the similarity of the Berkeley theme to the motif of the second movement, the ‘Marcia funebre’, of the ‘Eroica’. Even if this possibility cannot be proved, it seems highly plausible – and it raises questions about the interpretation of the Berkeley piece: should it be played with the characteristics of a funeral march in mind? It certainly can be, even though this seems to conflict somewhat with the dynamics, which indicate forte from the very beginning rather than the mysterious pianissimo that is indicated in the Symphony.

There are also exciting traces of a similar theme in Berkeley’s only other similar work for a solo instrument, the Theme & Variations for Violin Op. 33, from 1950. Although, overall, the themes are noticeably different, the first bit of the motif is almost identical in both pieces, and can be heard again clearly in some of the variations. The echo of the ‘Eroica’ theme is less marked in the violin work than it is in the guitar work, but it can still be heard. If Berkeley did indeed borrow Beethoven in his guitar Theme & Variations, he may have been deliberately referring back to his earlier Theme & Variations for Violin, or perhaps the motif had simply become a favourite. Here are the first nine bars of the ‘Adagio’ from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3:

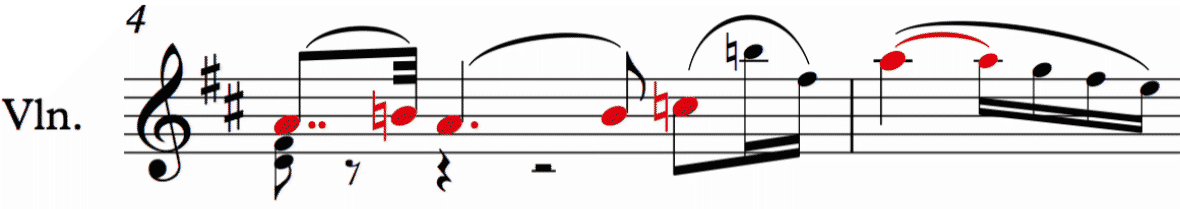

And this is an edited excerpt (bars 4-5) from the main theme of Berkeley’s Theme & Variations for Violin:

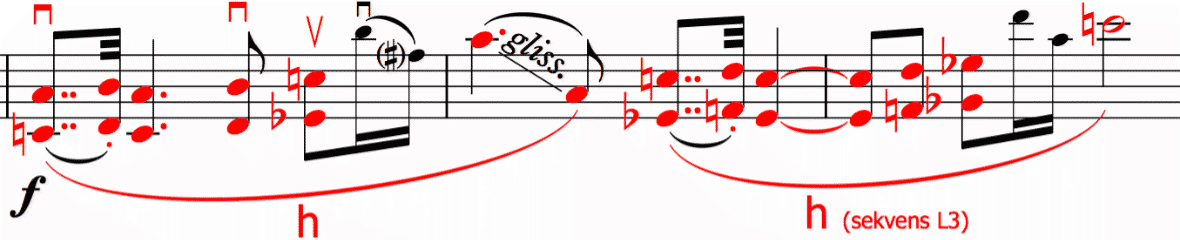

The next example is an edited excerpt of bars 32-34 from ‘Variation III’ of the same work:

After comparing all these three pieces and considering the fact that Berkeley wasn’t a Beethovenian, the similarities seem to indicate either a coincidence or a subconscious recycling of a theme once heard and never forgotten. Either way, they still remain remarkably similar after all, and the conscious thought of that considerably adds excitement to the interpretation of the piece.

Returning to the guitar work, in the first variation the main theme is dissected and repeated in pairs, thereby augmenting the melody, while the lower voice keeps cascading with its variations of the a1-motif. Whether or not to uncover the original melody line from all the lower voices, with its many arpeggios and scales around it, is perhaps the main puzzle of this variation. The question often faced in a work of theme-and-variations is whether the appeal of ambiguity should overrule the possibility of a clear reference back to the main theme. Since this is a recurring dilemma, it might be more useful to consider this variation in the context of the rest of the piece. While it is tempting to make every reference back to the original theme as clear as possible, that might risk the overall integrity of a variation as a whole. Especially since it forms, together with the fifth variation, a pair of dynamically strong and rhythmically steadfast pillars as a foil to the more sensitive variations of the rest of the work.

In contrast to the first variation, the second has the character of a humoresque and is perhaps well-suited to a free and playful style of playing. This is often how it is portrayed, but apart from the quite high tempo marking, there are no literal indications by the composer to support this, and perhaps playing it very legato can also be suitable. This time the main theme appears in the lower voice but more clearly than in the first variation. Notably, it also follows the Theme’s overall form (the only variation to do so).

Variation III consists of almost constant demisemiquavers that create a sort of tremolo sound, though it also bears the lowest tempo marking and is very tempting to play faster than the indicated fifty beats per minute. Its dynamic range from pianissimo up to only mezzoforte demands a certain restraint, while the mood returns again to the mystic, swelling and almost questioning feeling. Although fingered to use double strings to play the melody in unison, it can also be played using the tremolo technique in the right hand to keep the sound more consistent throughout the variation. To play the melody in unisons does add an interesting flavour to the tone, but in the end, I personally settled on a three-fingered tremolo solution on one single string to be able to vary tone colour and dynamics independently from the left hand’s limitations.

Variation IV switches several times between the time signatures 6/8 and 3/4 and creates a lovely swaying and soothing atmosphere. The lower voice is smoother in tonality this time, although still not really resting anywhere and thus maintaining a soaring sensation. Although rhythmically well hidden, the melody can be found in the exact original tones.

Perhaps the most powerful and majestic variation is the fifth, which the guitarist David Russell has described to me as ‘glamorous’ and ‘majestic’. ‘This’, he said, ‘is where Berkeley is winning!’, which emphasizes the importance of distinguishing the fine line between playing something ‘glamorously powerful’ rather than ‘angrily powerful’; for me the former adds a very fitting quality in this case. Additionally, an idea by Chris Stell was to dare to significantly hold out on the fermata in the third bar. This might sound obvious, but many interpretations disregard that fermata, yet it works beautifully in capturing the excitement of the unresolved beginning which then has to start again to climb just a little bit higher the second time.

Finally, the epilogue rounds this piece off with a steady ‘bell sound’ accompanying the main theme. This quite meditative variation clearly reflects the original theme, and in the last six bars it returns to the very first opening gestures of the entire piece, the broken ‘a1’ chord. It is central throughout the long and final phrase until it finally blends together and finishes off with the minor third harmonics. Although more technically sensitive and risky, the last harmonics can be played and plucked simultaneously with the right hand, to allow the left hand half-bar of the last chord to keep it ringing. Having them both ring out together may give the sense of more closure to the piece, compared to letting the chord go and having the harmonics sound alone, perhaps seeming more like a final question mark. To me, the choice between these two alternatives completely determines the final sensation of the piece. It is this kind of ambiguity that I find most intriguing with music, which is why playing this piece still feels like an adventure, with a taste that is continually fresh.

It’s been a joy to immerse myself in the literature I consulted for this project. In a way, the most rewarding part has been the discovery of new areas of the guitar world, together with the insights into the life of a twentieth-century composer. Similarly, exchanging ideas with experienced musicians has opened up new and passionate points of view. Besides, when a piece is relatively unknown and often overlooked, with very little writing about it and only a handful of recordings, it adds a wonderful mystique to the process of deciphering the music.

Whether you are a guitarist, another instrumentalist or just a music lover, my hope is that this essay can offer an interesting insight into an interpreter’s exciting and challenging task of portraying a truly original piece of music.