Studying composition with Lennox Berkeley at the Royal Academy

Composer Michael Elliott recalls his studies at the Royal Academy of Music as one of Berkeley’s first students

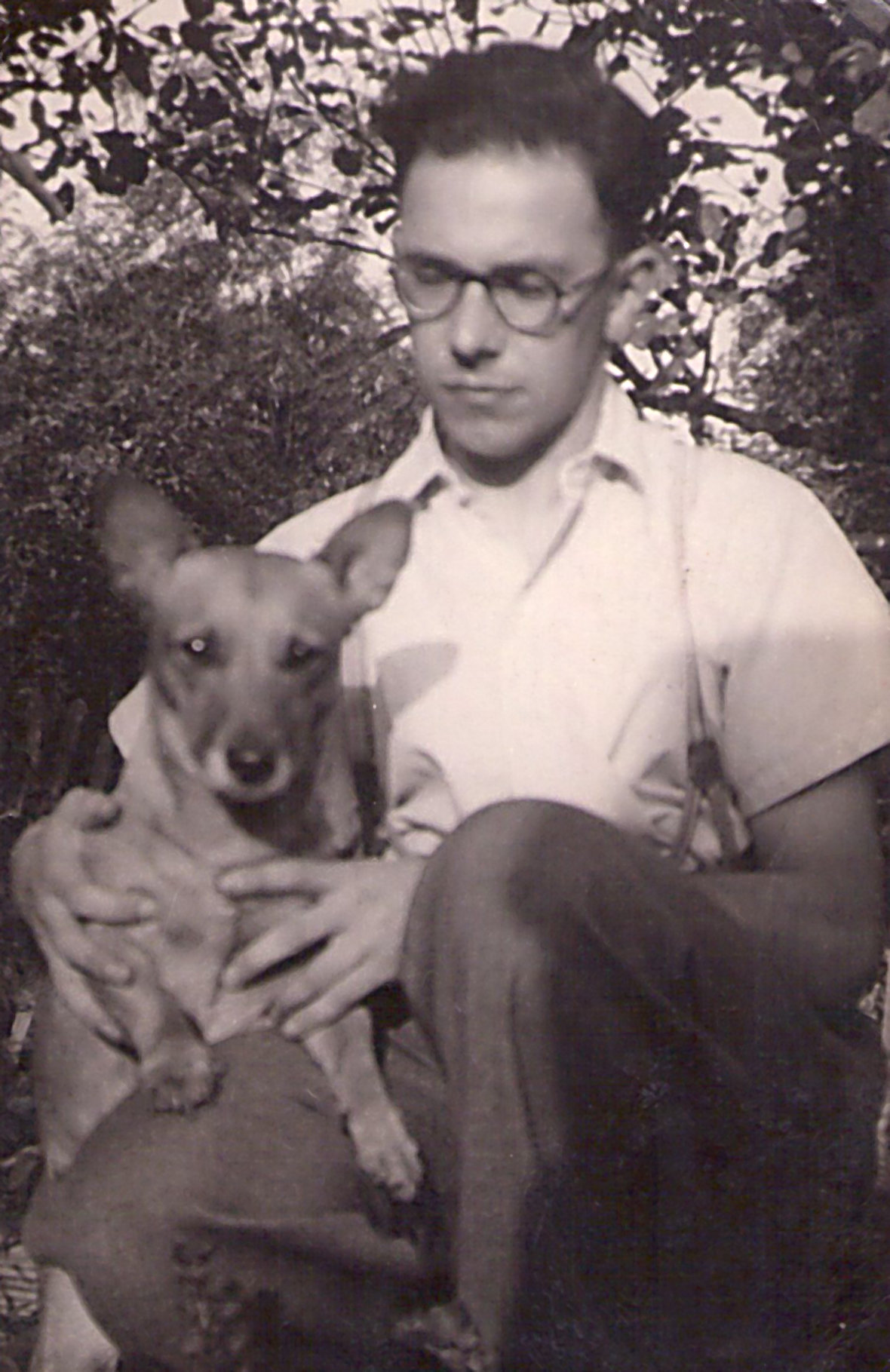

From ‘Bevin Boy’1 to music student in six months is quite a transition. I achieved this in 1945 when my year commenced working underground in a mine in Maesteg (Glamorgan), and in September enrolling as a student at the Royal Academy of Music. I previously had piano lessons and worked through the grades. As for composition I had no help or criticism, but for my entrance audition I played a set of variations I had composed and the examiner seemed to like them. Being ‘clever’, I had written the variations followed by the theme.

For the first three months Hubert Clifford2 was my tutor for composition, but in December 1945 he left to go to Australia and I had the good fortune to be placed with the famous Lennox Berkeley for composition.

First impressions were of a gentle, sensitive man who did not want to impose his ideas, but rather allow both parties to review and discuss any difficulties or problems in writing music of a genuine and original kind. Lennox suggested but never forced ideas, and after a few weeks I felt I had an honest and helpful mentor. One of his remarks I especially remember: when a doubtful passage or bar seemed to him to obtrude and spoil the flow of the music he would say, ‘If in doubt then try it without.’

Sometimes by simply omitting a passage altogether, the problem would indeed be solved. At other times it appeared that what came before or after the doubtful bars constituted the problem. Nowadays there is another saying, ‘Less is more’ – and that certainly applied to Lennox’s way of teaching, and, of course, his way of composing.

One of the most helpful ways a student composer can gain experience is by the sharing of ideas and the actual performance of original works. There was in existence at the Academy a Composers’ Club. We usually met monthly and played (or persuaded other students to play) our latest endeavours. This was very salutary, and at times quite a devastating experience. What sounded good to your own ears sounded very different when performed before other critical ears. Lennox came regularly to these gatherings; he said little but listened intently. His presence gave the work a more professional and worthwhile feeling. His attendance was always appreciated and subsequent words of encouragement were invaluable.

Most of my own compositions were for piano solo or voice and piano. Later I wrote choral works, a cappella and some chamber music. I have never been enthusiastic about composing orchestral music, and I feel more comfortable at a concert in the Wigmore Hall than in the Albert Hall.

Lennox suggested I should write some music in various forms and moods, such as sonata form, fugal, lyrical, dramatic or operatic. This was his way of encouraging the pupil to develop a genre and style that highlighted the talents and performance of the novice composer.

When I was leaving the Academy Lennox asked me to keep in touch and let him know what I was writing. That, of course, was typical of his generous spirit and genuine interest in those he had previously helped and motivated.

I realised I was not gifted enough to earn my living through music and so I trained as a librarian, and that became my lifetime career. I certainly could not have provided for a family as a piano teacher, but I found a satisfying (if not exciting) way of life with books. However I never stopped writing music and even now, at the age of 87, I am planning a set of 24 Epilogues. I have reached number 17, so needs must make haste if I want to complete the project!

In another example of his generosity of spirit, Lennox was asked by Chester’s to write some short pieces for oboe and piano, and, on finding he did not have time – as, presumably, he was writing other things – he asked me to write something, and submit it to Chester’s. I was of course very thrilled to be asked. and even more excited when they accepted them and agreed to publish them. The first and only music I have ever had published.

However for me the most important thing is the actual writing of the music, the thrill of creating. Naturally if someone shows an interest, and perhaps a performance follows, then there is tremendous satisfaction.

I thank God I had such a sensitive and gifted musician to guide my early days in writing music. Lennox was not a pushy or arrogant person, but a composer who knew his strengths and wanted to share them with others.

I am very glad to have found the Lennox Berkeley Society: it gives me a chance to renew my appreciation of the man and his work, and to meet other Lennoxites.