A look back at the funerals of Lennox Berkeley and his friend Benjamin Britten

Tony Scotland offers a last word about Lennox Berkeley and Benjamin Britten.

Lennox Berkeley’s intimate relationship with Benjamin Britten came to an end at Christmas 1938 after a row at Snape Mill when he was rejected in favour of the eighteen-year-old Wulff Scherchen, but the friendship continued till the end of Britten’s life. It was relegated to a lower place, and subject to Britten’s customary whims, but it lasted and was important to both, largely because of Berkeley’s loyal admiration of Britten’s genius, and his willingness to accept that a little bit of Ben was better than none at all.

It’s significant that when the Berkeleys’ first son, Michael, was born in 1948, Britten agreed to become a godfather – and played the part conscientiously, and with love. Lennox was so impressed that when he drew up a Will in 1949 he appointed Britten as legal guardian of the baby Michael, in the event of Lennox’s dying at the same time as Freda. Twelve years later, by which time two more Berkeley boys had arrived – Julian in 1950, Nicholas in 1956 – Lennox repeated his intention, in a new Will, appointing Ben as ‘Guardian of my infant children’. As I wrote in my book about the Berkeleys, this was an unusual arrangement to have made in those unenlightened days when child-rearing was still very strictly conventional.

Quite apart from the qualms that some parents might have had about Ben’s reputation, the idea of entrusting a baby boy to a couple of musical bachelors would have seemed utterly impractical, however much Ben and Peter might have enjoyed being parents.

The architect and designer John Greenidge, Lennox’s companion at Oxford and Paris in the Twenties and Thirties, may have been his oldest and closest friend, but Britten was the friend whose opinion mattered most. So it’s hardly surprising that Lennox felt he had lost a part of himself when Britten died in 1976. This is how he recorded it in his diary:

Ben, after a worsening of his heart condition, died on December 4. It seems that he was wonderfully serene, showing great courage and patience during his last weeks. It’s consoling to know there is general agreement that he was the greatest musician this country has produced in recent times. Unfortunately I saw very little of him in the last few years, but I remember so well the happy and exciting times we had together when I first knew him.

The news was announced the following day, and Lennox appeared on television that Sunday night, paying a personal tribute. Another old friend, the writer James Lees-Milne, was watching, and made a note in his diary:

Lennox came on the television, [and was] asked impromptu for his first memories of Britten. So good he was, natural and unhesitant. Told how when they wrote some songs together – they were abroad in Spain, I think [in Barcelona, on Mont Juïc, during the 1936 Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music] – Britten was listening to a man singing in a café. On the back of an envelope he jotted down the melody of the folk song. It was to be the theme of their joint composition [‘Mont Juïc’, a suite of Catalan dances for orchestra].

Britten’s funeral took place in Aldeburgh Parish Church on 7 December 1976, followed by burial in the churchyard. And in the spring of the following year there was a memorial service in Westminster Abbey. Peter Pears read the Bible story of God testing Abraham’s faith by commanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac, and the music included the slow movement of Schubert’s String Quartet and Purcell’s choral anthem Hear my prayer, O Lord. Lennox and Freda were there, and Lennox wrote in his diary afterwards that the music was well performed, even though the Schubert was lost in the great spaces of the abbey. And he went on:

I’m rather against Memorial Services; one of the advantages of being a Catholic is that one can ask for a simple Requiem Mass in Latin with the plainsong, and that the emphasis is on asking for God’s mercy rather than having panegyrics, well meant but less suitable. I always think of Francis Poulenc, who asked to have just such a service, and not to have any of his own music sung, but added that he would like the bells rung ‘pour emporter mon âme’ [to carry away my soul].

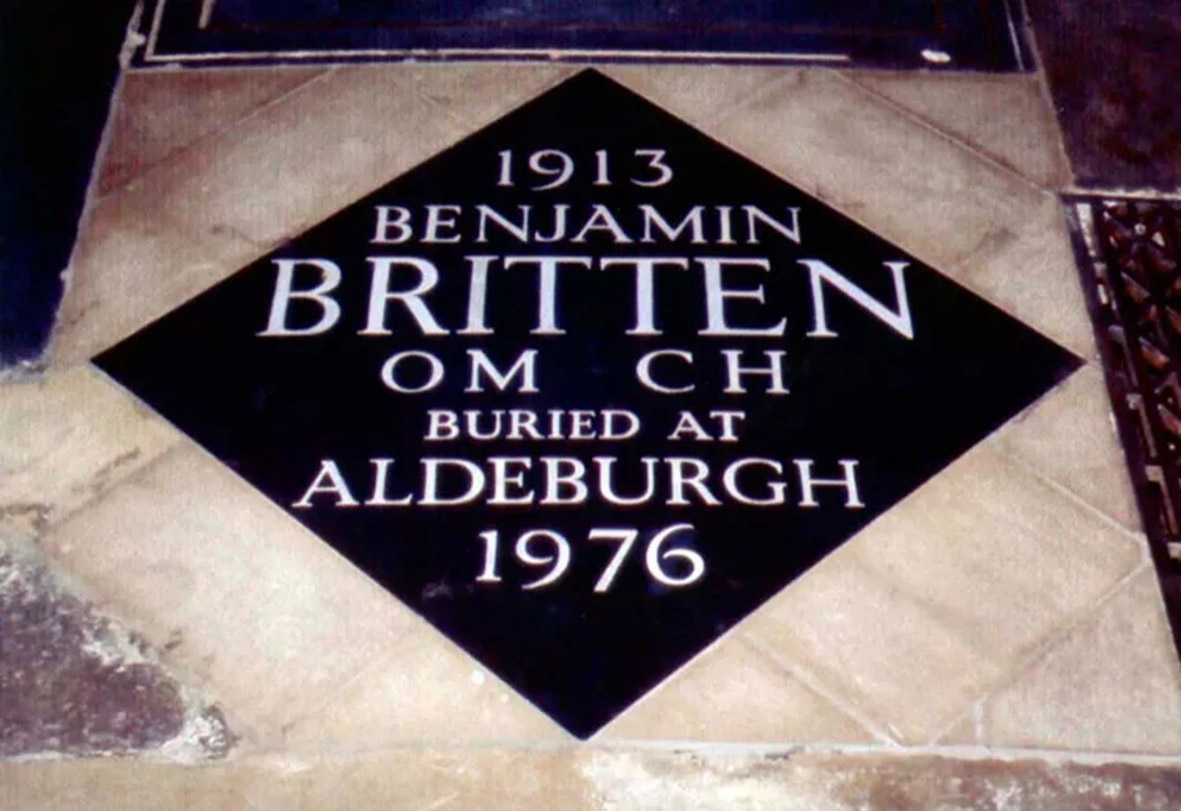

Another year on, Lennox was asked if he would unveil the memorial stone for Ben’s tomb in Westminster Abbey. He won't have known but he was in fact the abbey’s third choice for this honour – after the Prince of Wales (the present King) and Peter Pears, both of whom, for various reasons, turned it down. And that wasn’t the only backstage hiccup, as the Residentiary Canon of Westminster at the time, the Rev. Canon Trevor Beeson, recalled in his diary on 21 November 1978, the eve of St. Cecilia’s Day, the anniversary of Britten’s birth.

The memorial stone for Benjamin Britten was duly unveiled this evening in the course of a very splendid memorial concert in which we heard some of Britten’s finest music. However, it was highly embarrassing to discover not long before the start of the concert that a mistake had been made over the dates on the stone. Instead of 1913–1976 it has 1913–1977. Just how this came about no one seems to know; at least no one is prepared to accept responsibility for the error. The stone, which is close to those of Elgar and Vaughan Williams, will of course have to be taken up and completely re-done, at a cost to the Dean and Chapter of about £2,500 I fear.

And Canon Beeson’s eye-witness account doesn't end there. It seems that although there was general agreement about the rightness of honouring Britten in this way, there was disagreement about how to pay for it. His diary reveals, that ‘the executors of the Britten estate, who must be handling a great deal of money, were unwilling to release any for this purpose, and in the end the Worshipful Company of Musicians found the money.’

By a curious, and perhaps typically idiosyncratic, series of events, the remains of Lennox himself have never been formally laid to rest. According to the findagrave website online, they are buried in the churchyard of St. Peter and St Paul at Yattendon in Berkshire, but they’re certainly not; nor is there any reason why they should be. Yattendon plays no part in Lennox’s story, though it’s a nice coincidence that it was once the home of an eighteenth-century musician, George III’s dancing master, Sir John Gallini, who is buried in the churchyard and has a memorial tablet in the church.

Lennox died in St Charles’ Hospital, Ladbroke Grove, on 26 December 1989 and the funeral was held in the Church of St Mary of the Angels, Bayswater, on 4 January 1990, when Father Michael Hollings offered a Requiem Mass in the Old Rite. His remains were then cremated at Golders Green. Quite soon afterwards Lennox’s widow, Freda, moved into a mansion block in Bayswater. Uncertain what to do with his ashes, she left them in Little Venice, where she and Lennox had lived for forty-three years. At the kind suggestion of their old friend, the Vicar, Father John Foster, the ashes were placed in a jar under the altar of his eighteenth-century church, St Mary’s, Paddington Green.

Following the Church of England’s decision, in 1992, to ordain women priests, Fr Foster converted to Catholicism, and later became a priest. Concerned about the propriety of handing over St Mary’s to his successor with a Catholic under the altar, Fr Foster returned the ashes to Freda, who then placed them in an oriental urn on Lennox’s piano in her new flat.

In 1994 the Berkeleys’ old friend, the writer James Lees-Milne, proposed a nostalgic trip to the south of France, and Freda seized on the chance to scatter some of Lennox’s ashes on his parents’ graves in Nice. Lees-Milne has left a touching, and at times hilarious, account of this unconventional pilgrimage which he and Freda made in March 1995 with two other old friends, Lady Dorothy (‘Coote’) Heber-Percy and Lady (‘Billa’) Harrod. Unable to find the right graveyard, and with time running out, they sprinkled Lennox’s ashes in what turned out to be the wrong place – and the wind blew them back over their shoes. Freda decided to bring the rest of the ashes home, to the urn on the piano, where they remained till shortly before her death, when she transferred them to a sealed envelope in her desk. She hoped that it might be possible one day to bury them in Westminster Cathedral, in memory of Lennox’s long association there, as composer of liturgical music and father of two of its choristers. But on clearing the flat after her death, the family were unable to find the ashes, and they have never reappeared. However it’s hoped that it may still be possible to arrange some lasting memorial in the Cathedral.

Perhaps it’s a fitting conclusion to the story of Berkeley and Britten that, despite their different denominations, despite their different ages, despite their different domestic arrangements, they came together again in 2019, when all Lennox’s literary manuscripts and other papers were deposited at the Britten Pears Library in Aldeburgh. These included personal letters to Britten, and the final fair copy score of the Concerto No. 1 in D Major for Piano Solo and Orchestra, which Britten composed for the 1938 Proms, and dedicated, and presented, to Lennox. It dates from the happy summer of 1937 when the two composers were planning to live together in a converted windmill in the village of Snape, and the less happy summer of 1938, by which time they were settled in the Mill – but with young Wulff Scherchen as part of the picture. Lennox was proud to be the dedicatee of the new concerto, which he said he felt he really deserved ‘as Ben’s greatest admirer.’ And he returned the compliment in the autumn by dedicating to Ben his own Introduction and Allegro for Two Pianos and Orchestra. He had hoped they would play this together at the Proms in 1939, but by then Ben had gone to America with Peter Pears, and the premiere had to be delayed till 6 September 1940, when Lennox and William Glock were the soloists with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Henry Wood.