Lennox Berkeley’s ‘Gibbons Variations’ revived by London Choral Sinfonia

Conductor David Wordsworth writes about Lennox Berkeley's ‘Gibbons Variations’, and its first-ever recording by the London Choral Sinfonia

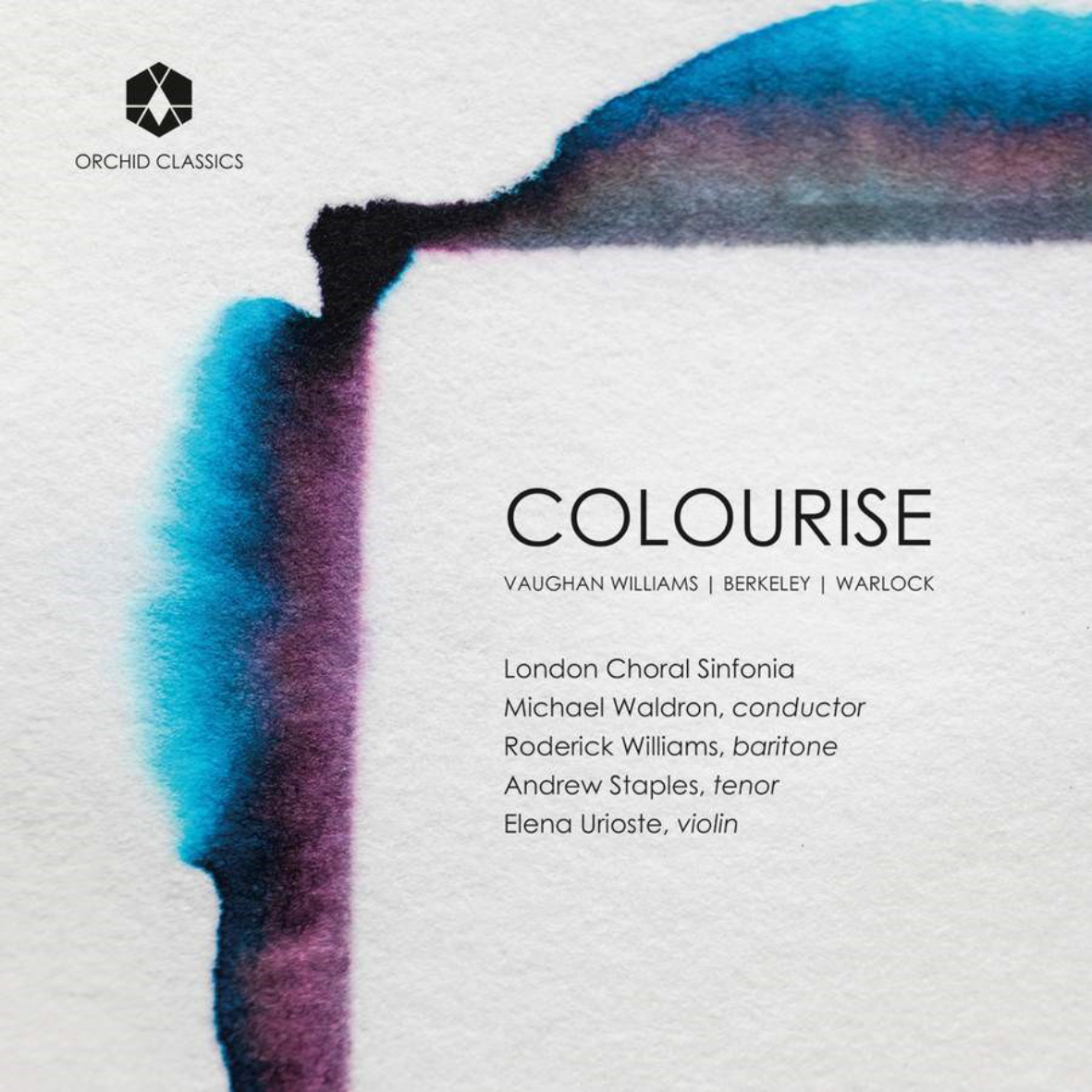

The proliferation of recordings of music by Lennox Berkeley over the past twenty years or so has been more than welcome, but there are still gaps to be filled, as is amply demonstrated by this recently released CD of the Variations on a Hymn by Orlando Gibbons, by the London Choral Sinfonia and the tenor Andrew Staples, conductor Michael Waldron.

The catalyst for this recording, as Michael Waldron explained in the 2021 Journal, was the chance discovery of a vocal score of Berkeley’s piece, which, after an unsuccessful premiere at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1952, with tenor soloist Peter Pears and conducted by Benjamin Britten, all but disappeared. An uncharacteristically contrite letter of half-hearted apology from Britten to Berkeley after the premiere suggests that it was a less than satisfactory performance, but such is the fate of so many works at their premiere and this doesn’t explain why the Gibbons Variations sat languishing on a publisher’s shelf for so many decades.

Great claims are often made of music that has been ‘re-evaluated’, but this is really quite a discovery, quintessential Lennox Berkeley, and coming from that wonderfully fertile post-war period, that saw some of Berkeley’s best music – the Stabat Mater, the Four Poems of St Teresa of Avila, the Piano Concerto, the Horn Trio, not forgetting his operas Nelson and A Dinner Engagement.

The performance does the work proud – diction from the choir is exemplary, rhythms are tight and focused, from the viol-like introduction when we hear the theme for the first time, to the more vigorous variations, and the masterly integration of the organ into the orchestral texture – not an easy thing to achieve: plaudits for the producer as well as the conductor.

We travel through a wide range of emotional and spiritual moods, each highlighting a particular combination of choir and instruments – choir and strings, organ solo, unaccompanied choir, strings by themselves; only at the end do the forces come together. The tenor Andrew Staples features in two of the most magical moments of the piece – he has his own variation, an extended aria, that sounds like a close relation of the St Teresa Poems and couldn’t be by any other composer, inhabiting as it does a very personal spiritual honesty and intensity. On the one hand it’s perhaps surprisingly chromatic, but on the other natural and understated – most beautifully sung. Then in the final bars of the work there’s one straightforward resolution that sees the tenor soloist rise a semi-tone to join the choir and orchestra in the consoling key of D major, and this alone is worth the price of the CD! The easiest thing in the world on paper, but here delivered in such a way that one can almost hear a sigh of relief from the performers. Let’s hope this recording will result in a resurgence of interest in the Gibbons Variations – the forces are not large and the choral writing is well within the capabilities of a good choral society.

As for the rest of the CD, Roderick Williams is in fine voice (when is he ever not?) in the Five Mystical Songs by Vaughan Williams. This version (with soloist and choir accompanied by piano and strings, rather than the usual full orchestra) is also unaccountably and remarkably a premiere recording, and works very well. I’m not entirely sure how Warlock’s Capriol Suite fits in to this programme, charming though it is, although the conductor makes a connection with Ravel in his notes, thereby, I suppose, linking both Berkeley and Vaughan Williams.

It is probably best to draw a veil over The Lark Ascending, at least as far as the present writer is concerned. This is certainly no reflection on the piece, or on either the choir or the violin soloist (Elena Urioste) who plays beautifully, but the more I listen to Paul Drayton’s ‘arrangement’ for violin and choir of this iconic work the more I ask myself, quite simply, why? As George Hall points out in his notes, this piece has appeared in various guises over the years, but I can’t believe that even RVW, as practical as he was, would have approved of his Lark soaring over the words of George Meredith’s poem hoisted on to the choir, amid a collection of Mms, Doos, Uhs and Ahs.

Still, for the readers of this Journal, there can be no doubt that the focus of interest will be the Gibbons Variations – and be in no doubt this is a must!