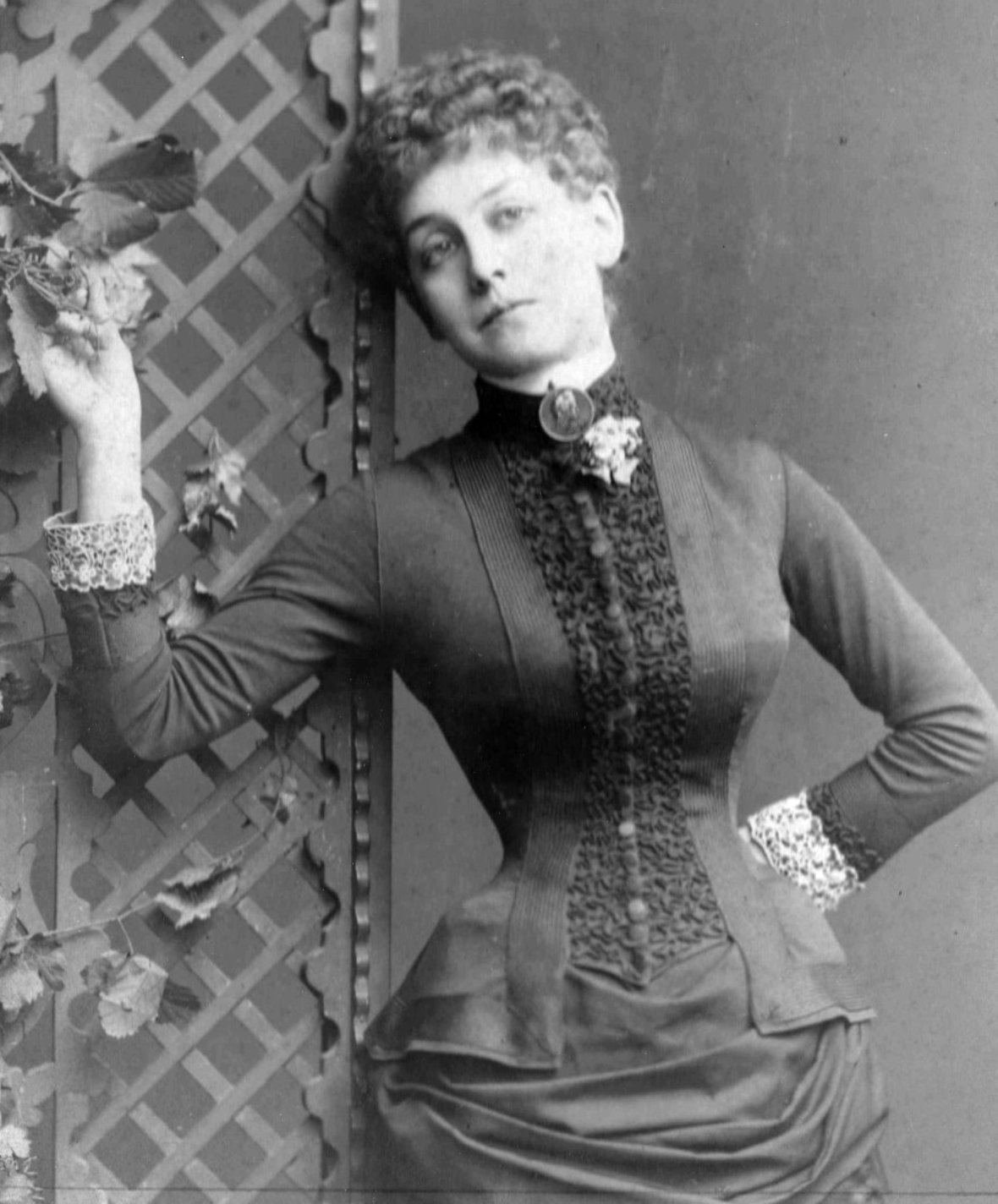

Musical comedy singer Edith Brandon

Tony Scotland reveals Kate, Countess of Berkeley as the musical comedy singer Edith Brandon

In the dying years of Victoria’s reign, as the stays of popular entertainment loosened, it became fashionable for sprigs of the aristocracy to haunt stage doors, to woo the chorus girls with flowers and champagne – and sometimes to take them home as brides.

The first showgirl to marry into the peerage was Rosie Boote, a Gaiety Girl who won the heart of Geoffrey Taylour, a lieutenant in the Life Guards, and became the Marchioness of Headfort. When the burlesque artiste Connie Gilchrist, daughter of a laundress, ‘burst on the Gaiety audience in a skipping rope dance’,1 Edmond Fitzmaurice fell wildly in love and made her the 7th Countess of Orkney. The music hall singer Belle Bilton captivated William le Poer Trench, Viscount Dunlo – they married in secret, and in due course Belle became the Countess of Clancarty. Dorothy Haseley, aka ‘Dolly Tester’, doyenne of the Theatre Royal, Brighton, married the Marquess of Ailesbury, generally known as the Coster Marquis, on account of his foul language, coarse manners, extraordinary clothes of ‘cord fustian’ and an equipage drawn by a donkey.2 The 7th Earl of Stamford and Warrington married, first, the daughter of his bootman at Cambridge, one Bessie Billage, and, when she died young, of a seizure, he married a black-eyed gypsy bareback-rider called ‘Kitty Cocks’, celebrated for riding through hoops of fire.3 And in 1887 Edith Brandon, a sedater star of musical comedy, became the Countess of Berkeley, first wife of Lennox’s uncle Randal, research scientist and author of an eccentric golfing manual.

Their new coronets notwithstanding, all these former actresses were regarded as beyond the pale by society, and shunned at Court. The Los Angeles Herald, eager to have a go at the English aristocracy, reported on 8 December 1901:

These peeresses enjoyed some celebrity among the golden youth of the metropolis before becoming the consorts of hereditary legislators, and it is owing to their ante-nuptial fame that the king and queen [the new King George VII, who was not yet crowned, and his beautiful wife, Alexandra of Denmark] object to their presence at Court and at the Coronation [scheduled for June 1902, but postponed for two months because of the royal stomach].’

It goes without saying that the king himself was not without similar ‘fame’: throughout his life he kept mistresses, some say as many as fifty-five, including the actresses Lillie Langtry and Sarah Bernhardt, the singer Hortense Schneider and the courtesan Giulia Beneni, as well as Lady Randolph Churchill, Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick, Alice Keppel and the rest.

Despite the taint of her association with the Victorian theatre, Edith Brandon was probably not alone in becoming a model peeress – after all, these women were actresses, showgirls, and playing parts was what they did. But Edith Brandon does seem to have had a special quality all her own, and this was generously acknowledged in a colonial newspaper:

The new Countess of Berkeley was formerly Miss Edith Brandon, a clever and charming actress, against whom not even the idle tongues which wag so freely about any and every woman who adopts the stage as a profession have ever had aught but good to say. No one who knew her during her stage life will grudge her a social honour which she is by no means incompetent to support with grace and dignity.4

Born Kate Brand, on 15 April 1854, Edith Brandon was the elder daughter of William Farries Brand, a Scots-born sack merchant in Liverpool, by his wife Martha Binns née Dean, a Methodist cotton weaver. It’s not known how she started her musical career, but it’s likely that it was music that brought her together with the man who became her first husband, Arthur Jackson.

The son of a piano tuner in Brighton, Jackson was then studying piano and composition at the Royal Academy of Music in London. They married in Islington in 1874, when Kate was twenty, and Arthur twenty-three. In 1878 he was elected Professor of Harmony and Composition at the Academy, and not long after the birth of their first and only child, Sybil Dean, they moved into a large flat in Oxford and Cambridge Mansions, Marylebone.

Despite the demands of his teaching Arthur Jackson found time to write a considerable number of significant works, including a Magnificat for voices and orchestra, two Masses for male voices, the cantata Jason and the Golden Fleece, a Piano Concerto, a Violin Concerto, and various pieces for orchestra and for piano solo. But in 1881, at the age of only twenty-nine, and still far from his peak as a composer, he contracted tubercular meningitis and suddenly died.

His widow Kate, needing an income, adopted the stage name of Edith Brandon and launched a career as a singing actress in comic opera. Perhaps through her husband’s contacts she attracted the attention of the composer and theatre manager Thomas German Reed, who provided musical plays ‘of a refined nature’ for the entertainment of families. Many of these were written by himself, several of them to libretti by W. S. Gilbert. In one of the German Reed Entertainments, in Hastings in the summer of 1881, Edith was cast in ‘a pretty little piece’ written by Hamilton Clarke to words by Arthur Law, called Cherry Tree Farm. The ventriloquist and showman Robert Ganthony, happened to be staying in a house looking down at the rear of the Hastings Music Hall during the run of Cherry Tree Farm. One hot night the blinds of the first-floor hall were left open and he and his wife could see, through the open window of their sitting room, that the stage footlights had been lighted.

Our curiosity made us keep an eye upon the hall. We did not wait long for an explanation, for Fanny Holland [the soprano and comic actress, later Mrs Arthur Law] entered left upper entrance with no dress on her shoulders, and a pair of curling tongs in her hand, followed by Edith Brandon from the opposite side, also in her stays and petticoat, and armed with a pair of curling tongs. They both came down to the footlights and conversed as they heated their irons and applied them to their heads.5

Four years later both Fanny Holland and Edith Brandon starred in a spectacular ballet and comic opera called The Lady of the Locket by William Fullerton at the Empire Theatre in London. The opera was set in Venice in the fifteenth century and involved ‘gorgeous’ costumes, ‘ear-catching’ melodies, five patter songs, and some ‘stupendously stupid music hall dialogue’. There was also a Grand March involving ‘picked men from the Coldstream Guards’, and a fetching scene in which, ‘for a frolic’, Fanny Holland and Edith Brandon impersonated each other.6

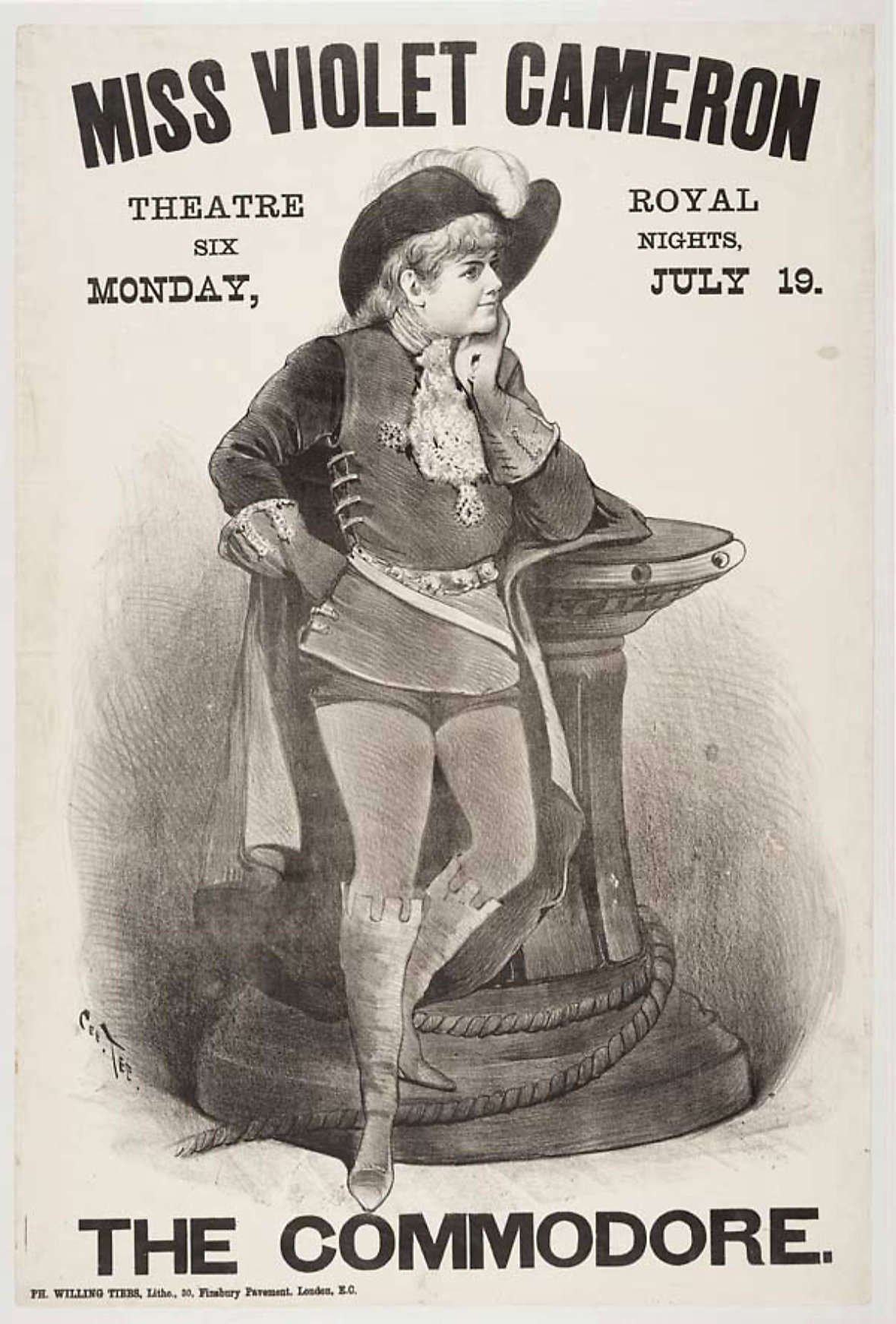

In 1886 Edith was invited to join a new comic opera company which was being set up by the singing actress Violet Cameron, with backing from her young lover, the Earl of Lonsdale. In their opening production of Reece and Farnie’s The Commodore (very loosely based on Offenbach’s La Créole), Edith played the part of Antoinette who foils a plot by her guardian, an old sea dog, to marry her off to his nephew, a freelance musketeer, played by Violet Cameron. And in the same collaborators’ burlesque Kenilworth (drawn from Scott, via opéra comique) she and Violet again shared the leads – Violet, a mezzo-soprano, in the trouser role of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who hopes to marry his admirer Elizabeth I, and Edith, a soprano, as Dudley’s beautiful but unhappy wife Amy Robsart who’s subjected to neglect, insult and finally death.

By the autumn of that year it was clear that Violet Cameron was pregnant. She announced that the father was Lord Lonsdale, whereupon her husband – a Moroccan tea taster – threatened divorce. To get away from it all Violet and her lover took the whole company on tour to America. Edith left her eight-year-old daughter Sybil in the care of her family, and joined the Company as ‘one of the so-called “charmers” ’ in the troupe of thirty-six. They made the six-day crossing in the Cunard steamship Aurania – with, by chance, General Booth of the Salvation Army, whose footsoldiers welcomed them ashore in New York to a chorus of Hallelujahs.7 The following day the next ship in from England brought the Moroccan tea taster – and Lillie Langtry, who’d had a dalliance with Lonsdale the previous year. The tea taster arrived with divorce papers, Miss Langtry brought the deeds to a house she’d bought on West 23rd.

Thanks to sensational publicity about the baby and the divorce and the presence in New York of all the protagonists, the Company drew full houses at the Casino Theatre on Broadway. In The Commodore and Kenilworth Edith and Violet repeated the roles they’d given with such success in Britain. But America hated both operas: Kenilworth was denounced for its ‘vulgarity and vicious commonness’,8 while The Commodore was said to be ‘one of the worst failures in the history of the Casino’.9 The New York Times concluded that The Commodore was ‘hopelessly dull even in comparison with the ponderous specimens of British burlesque heretofore made known to American amusement seekers’. Though the Company was ‘a well balanced and well trained body of artists’, it was so deficient in originality and cleverness, and so cheerless, that ‘20 minutes before [the three-hour entertainment] ended the audience commenced departing in platoons’.10

Within a month the Company was on its way home again, dispirited, ‘disgusted’ with American audiences and a great deal poorer.11 Once home, Violet Cameron gave birth to Lonsdale’s baby girl, and, on the advice of Queen Victoria the father left for the Arctic. Undeterred by either the American catastrophe or the baby, Violet took Edith and her ‘Charmers’ on a British tour with The Commodore and Kenilworth. But Edith Brandon wasn’t to remain with the Violet Cameron Company for much longer.

Among the audience at one, and probably more, of those New York performances was a young English naval officer, Sub-Lieutenant Randal Berkeley, Viscount Dursley, then serving on the corvette HMS Canada in North American waters. Randal was strongly drawn to the character of Antoinette, the pretty ward who finally wins the man she truly loves, and made his feelings known when he joined the Stage Door Johnnies clamouring for introductions afterwards. An intimacy grew up between him and Edith, whom he soon knew as Kate, and the following year Randal resigned his commission, in order to study chemistry – and to marry Kate, the widowed Mrs Arthur Jackson. The wedding took place in St. James’ Church, Piccadilly, on 9 November 1887. The new Viscountess Dursley was a widowed mother of thirty-three, Randal was only twenty-two. When Randal’s father died the following August Randal became the 8th Earl of Berkeley and Kate his Countess. But Randal’s claim to the title wasn’t formally confirmed till 1891, when the House of Lords re-heard the Berkeley Peerage case of 1811 and found in his favour.

For some time the Berkeleys lived at 15 Drayton Gardens in South Kensington, with Kate’s daughter, Sybil, then a teenager, and Randal’s eldest brother, Captain Hastings Berkeley, R.N., later to become Lennox’s father but still then a bachelor in his mid-thirties. Hastings had been invalided out of the Navy and was now working as a director of a Cornish mining company in the City.

Randal’s new title had brought no property, nor would he inherit any till the deaths of two elderly Berkeley relations, who, consecutively, owned Berkeley Castle and its vast estates. So he borrowed heavily in anticipation of his inheritance – so heavily that he was able to employ a butler, a cook, three maids and a nurse, and four more servants lodging up the road at No 21A Drayton Gardens. At Randal’s insistence No 15 was fitted with the new electric light. Hastings felt that this was unnecessarily extravagant and was not at all sure it would work, but as he told his fiancée, Aline Harris, at home in Nice, ‘Randal is very wilful, &, in fact, rather crazy on this point so he has had his way’. Hastings referred to his brother and Kate as the ‘Kittys’. Quite often Randal was away ‘geologizing’ (carrying out experiments, on location, for an improved method of determining the density of crystals); and quite often Kitty was ill, or shopping.12

In 1893 the Kittys moved to a large new redbrick house called Wootton Heath at Boars Hill on the Cumnor Hills south west of Oxford, which Randal, again with borrowed money, transformed into a grand Edwardian country house. He named it Foxcombe Hall but the locals nicknamed it Berkeley Castle; it’s now the south-east regional headquarters of the Open University. Meanwhile they waited for the unfolding of a fate which would bring them the real castle and its vast estates.

But Kate Berkeley never lived to see that happen. Suffering from a variety of diseases of the heart, lungs and kidneys, she languished in bed for months at Foxcombe, where, on 29 March 1898, aged only forty-three, she died; she was attended by her daughter Sybil, who was then nearly twenty.13 For some inexplicable reason it took another twenty-seven years to prove Kate’s modest little will, under which she left her few belongings, valued at £130 16s, to her husband Randal. By then he had married for the second time and was an immensely rich man, in possession of Berkeley Castle, 23,000 acres of farmland in Gloucestershire and Middlesex and the whole of the Fitzhardinge Estate in Mayfair, which included most of Berkeley Square and Berkeley Street, and eight adjoining streets. He and his wife, an American widow, Molly Lloyd née Lowell, spent a great deal of his inheritance on lavish living, with houses in America and palazzi in Italy, and two Rolls Royces – one a yellow landaulette with an armchair on a raised platform at the back so Randal could cruise around the estate, spying for poachers and trespassers; the other made of ice cream which motored down the length of his dining table delivering pudding. What was left of his fortune when he died in 1942 he willed, with the castle and the lands, to a distant cousin. He had long since broken off relations with his elder brothers, Hastings and Ernest – over a row involving a hedge across his golf course at Boars Hill – and he left nothing at all to their sons, Lennox and Claude. With no legitimate heirs, for Hastings and Ernest were born before their parents could marry, the title became dormant if not extinct.

It is sad that Lennox never knew his aunt Kate, 8th Countess of Berkeley, who would have been well qualified – as singer, showgirl and peeress – to play Her Serene Highness the Grand Duchess of Monteblanco in his opera buffa A Dinner Engagement, which pokes such gentle fun at the English class system.