Divertimento

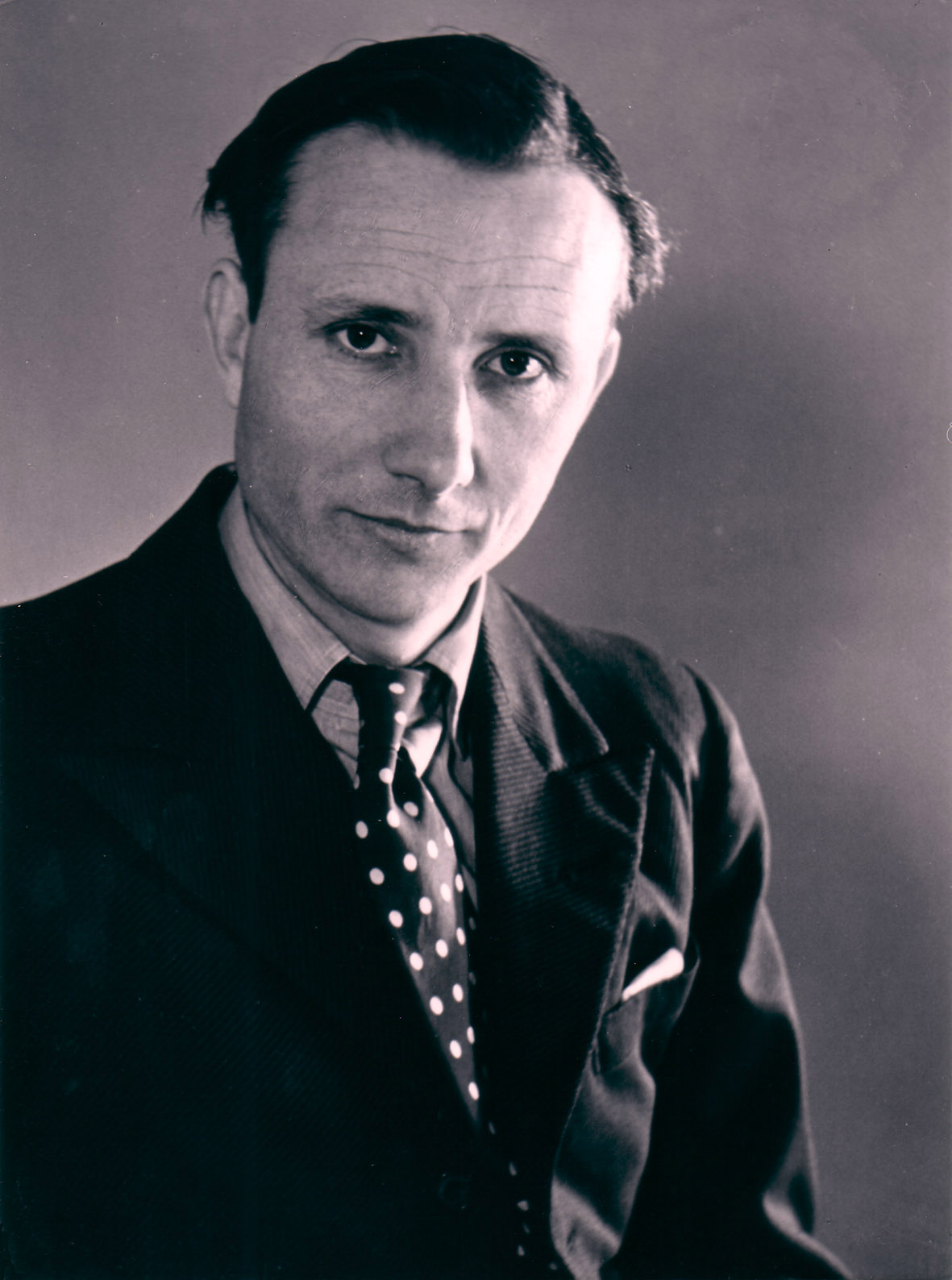

Tony Scotland examines a dossier on Berkeley’s ‘Divertimento’

A confidential file about one of Lennox Berkeley’s most popular works and its role in British cultural propaganda in the wake of the Second World War has just been released by the National Archives at Kew.

Documents in the file show that in 1948 the British Council and Berkeley’s publishers, J. and W. Chester, commissioned Decca to make a record of the Divertimento in B Flat (Op. 18) ‘for propaganda purposes’ (in the words of the contract), in connection with the promotion of British culture overseas.

The British Council had been founded in 1934 by Sir Reginald Leeper, later head of Britain’s Political Intelligence Department, who saw it as a means of promoting British interests abroad through what he called ‘cultural propaganda’; Hitler had become Führer that year, and to some in Britain, though not yet all, Nazism was seen as a threat which Leeper believed the arts could play their part in keeping at bay.

At first the Council’s propaganda campaign involved only theatre, literature and painting, but music was drawn in following the publication, early in 1942, of draft documents on Music Policy at the BBC. Of particular significance was a paper written by the composer Arthur Bliss, then Director of Music at the BBC (and Berkeley’s boss), who wrote that ‘A sense of music is a primal thing in mankind, and a tremendous force either for good or evil. Music is an ennobling spiritual force, which should influence the life of every listener’.

Within months the British Council began recording important recent compositions by British composers, with a view to disseminating them abroad as examples of Britain’s artistic vitality. E. J. Moeran’s Symphony in G Minor was the first work to be recorded. Then, in quick succession, came Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast, Bliss’s Piano Concerto, Bax’s Third Symphony and Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius.

When the war was over and the Council’s sponsors at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office decided to continue the work of the Music Advisory Committee, the Council’s Assistant Director, John Denison, proposed a recording of Berkeley’s Divertimento. Denison had been a horn player in the BBC Symphony Orchestra, when Lennox was building the orchestra’s programmes during the war, and probably played in the first performance of the work in October 1943 at the Corn Exchange in Bedford (where the orchestra was evacuated in the Blitz). Berkeley had written the Divertimento in April that year, in response to a commission from Arthur Bliss, who regarded it as ‘his national duty [as Director of Music at the BBC] to present a bigger proportion of British music’. The work is dedicated to Berkeley’s teacher and lifelong friend, Nadia Boulanger.

The orchestra Denison chose was the London Chamber Orchestra (leader David Wise), conducted by its founder, Anthony Bernard, who had been one of the first mainstream conductors to champion Berkeley’s orchestral music as early as 1925 when Berkeley was still at Oxford. The deal was that the British Council would pay Decca a total of £351 15s., of which Chester’s would contribute 25%, in return for 25% of the profits, plus twenty free copies of the two-record set. In addition Chester’s were to supply the full score and parts at a cost of three guineas. There is no reference to a fee for the composer, but presumably his reward was to come from the royalties on record sales.

On 18 February the Manager of the Artists Department at Decca, H. G. Sarton, wrote to John Denison at the British Council with a list of the players for the recording, and a note that Denison’s colleague, the violinist Theo Olof, ‘considered the back desks of Violin and Violas are rather weak’.

On 7 March 1948, Berkeley wrote to John Denison expressing his delight at this significant development in his new career as a full-time composer (he had left the BBC in 1945):

As you know, nothing of mine has been recorded as yet, so it is very exciting for me to think that it is really going to happen.’ He himself would attend the recordings on the 25th, and he hoped Denison might be there too. He had already been in touch with Anthony Bernard, and ‘we’ve decided that it will just go on four sides, though the third movement is going to be rather a squash!

The contracts were signed on the 23rd March, and the following day – the eve of the recording – Douglas Gibson, a director of Chester’s, wrote his own letter of thanks to Denison, trusting that the British Council’s efforts would be fully justified by results. Then, pressing his client’s suit with a commendable tenacity, he proposed a sequel:

May I suggest that when this is completed, the recording of the Piano Sonata by Lennox Berkeley might be considered, in view of its importance amongst contemporary works. I suggest that Clifford Curzon would obviously be the best artist to undertake it.

(Curzon, the dedicatee of the Sonata, had given the first performance at the Wigmore Hall on 22 July 1946, but in the event the contract was given to the New Zealand pianist Colin Horsley who recorded the work in 1959, in close collaboration with the composer.)

Five months after the Divertimento record was made, Decca asked Berkeley to write a programme note. On 28 August 1948, he sent one, with a covering letter:

Here is a brief account of the Divertimento … I think it says everything that needs to be said …

This work, which was written in 1943, is scored for a slightly reduced orchestra (double wood-wind, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 1 trombone, timpani and strings). It has no programme or story attached to it, being, as its title implies, written with the object of pleasing and diverting the listener. It is four movements – the first, ‘Prelude’, is in a kind of very condensed Sonata form, with two main subjects; the second, ‘Nocturne’, is in free form but close-knit, with considerable economy of material. After this comes a ‘Scherzo & Trio’ which is entirely classical in shape, except that the repeat of the ‘Scherzo’ is ‘telescoped’ and is, in fact, only about half the length that it was before. At the end of this repeat, the ‘Trio’ reappears for a moment, but is cut short after two bars by the final chord. The last movement is a Rondo’; there are twelve bars’ introduction, after which the movement follows the normal course. The main motif appears three times.

The Decca recording of the Divertimento appeared, as planned, on two 78 rpm discs with the number Decca AK 1882-3, and copies were duly dispatched to all overseas British Council offices which had been closed during the war, particularly in Europe, for distribution locally. The specific objective was to show that despite six years of war, British music was alive and well.

In the 1970s Berkeley himself conducted the Divertimento with the London Philharmonic Orchestra on Lyrita SRCS 226. Bernard’s Decca 78s are hard to find these days, but Berkeley’s later Lyrita recording is still available as a CD reissue.