Berkeley’s orchestral ‘Nocturne’

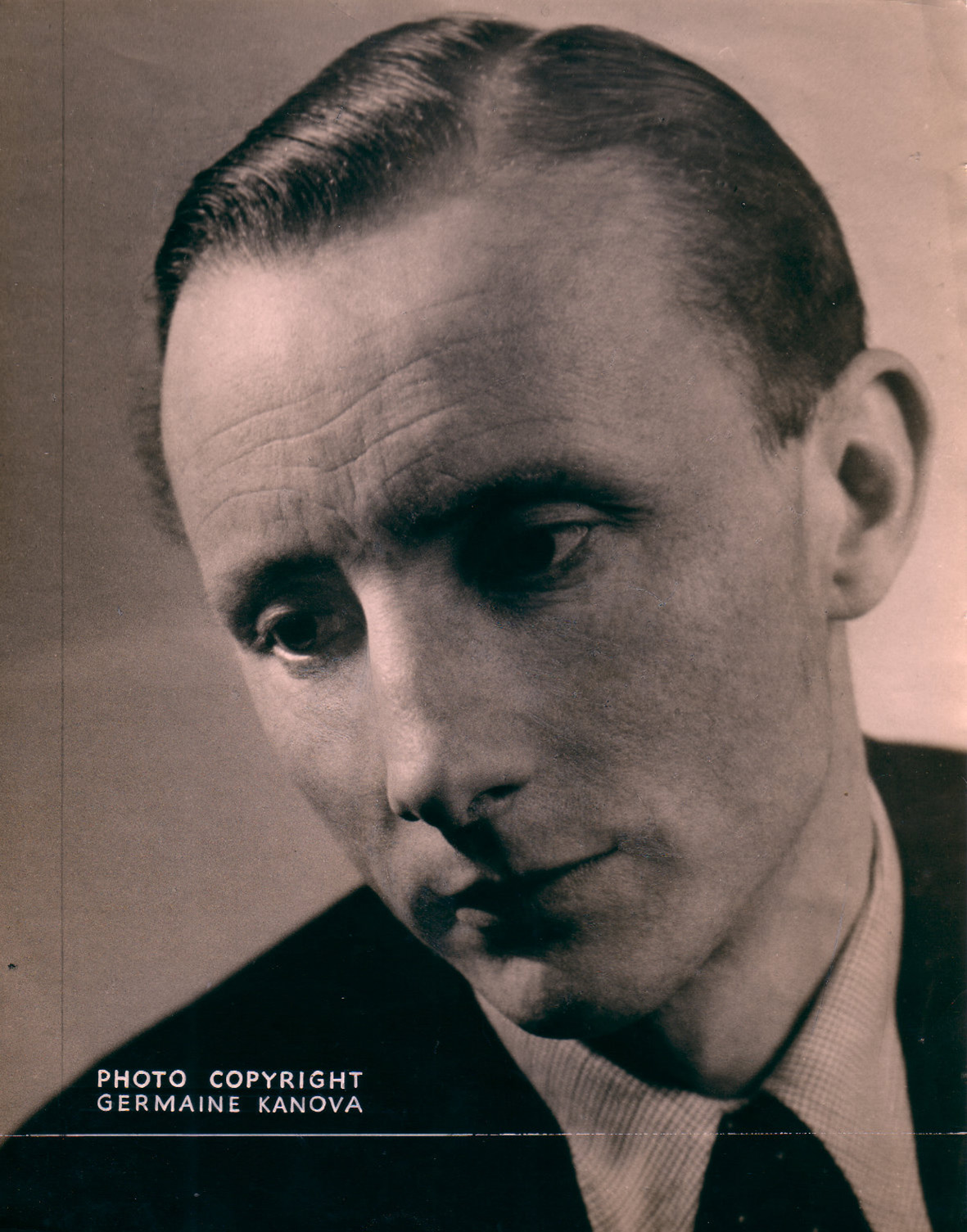

Rob Barnett explores Lennox Berkeley’s ‘Nocturne’ and his recurring use of night music.

Lennox Berkeley was in his early, and still formative, forties when he wrote the Nocturne for orchestra in 1946. A year earlier he had completed his Piano Sonata, the Violin Sonata and the Six Preludes for piano. A year later and he had asserted himself with the Piano Concerto (his first), Four Poems of St Teresa of Avila for contralto and strings, and the Stabat Mater for six solo voices and twelve instruments. Some of these works achieved a measure of exposure and recordings but not so the Nocturne. It is a work which, quite apart from its intrinsic merits, can be seen as a limbering-up for more ambitious scores to come and an expression of a questing and growing confidence. Fully formed, it inhabits a dreamy world, but this is a realm distant from the delectable romance of a nocturne by Chopin or Field. It is in the nature of a pilgrimage through something dark, fitfully heroic and uncertain.

The tenor of the piece might, in the wake of the Second World War, have spoken of an exuberant New Elizabethan future. This work feels more as if it belongs to the core war years; the same years that produced the Fourth Symphony by his contemporary Edmund Rubbra, and a work in much the same meridian as the Nocturne, Rubbra’s Soliloquy for cello and orchestra.

Nocturne is an overture-length piece of just eleven minutes’ duration. In its concision it is typical of the output of his maturity. However the often lush cinematographic intensity of the music leaves it standing apart. It has always suggested to me the miasmic aspects of the 1940s world of film noir. Its strong atmosphere and the generally andante pacing leave the suspicion that Berkeley might have cherished it as the slow movement of a symphony. It might have fared better in the concert hall had it not gone out into the world as a single, short, isolated statement. In that sense it parallels Samuel Barber’s almost contemporaneous Night Flight, which for years existed as a free-standing piece rather than the central movement of the American composer’s Second Symphony.

A soft pianissimo susurration from the strings enters in the form of a quiet but secure pulse. This figure is repeated throughout and soon recurs for the first time in the lower strings. There’s a gradual increase in complexity and intensity and a subdued fanfare is heard. A climax is attained with, at 2:26, the momentary shadow of Big Ben’s chimes. The music then fines down to chamber textures with the flute taking the lead. An upstart episode on the wider woodwind is heard before a quiet Sibelian ostinato sidles in. Harp swirls prelude the return at 3:34 of the pulsation from the start. Aspirational violins alternate with woodwind, stirring an emotional turbulence. From 4.27 to 4.36 the horns echo back and forth in what is a wonderful and eminent climactic moment. Things fall away, and the impetus is gently taken by the woodwind. The skein of sound becomes tonally ambivalent and a conspiratorial quiet takes centre-stage. A fitful heroism is voiced by the trumpet.

Another landmark episode follows at 6:00 in a moment that could have been plucked from Miklós Rózsa’s film score, The Lost Weekend. This is sustained for some thirty seconds, when another climax steps forward but is soon gone – to be replaced, after a distinct pause, by some surreptitious and meditative writing. A bereft, Ravel-like flute gently returns us to that almost immanent pulse motif and to pages of tonal complexity harking back to the work’s midway point. The woodwinds then seem to be stepping doggedly up a long casemented stairway. The sense is that this scene is being subtly limned in with trailing tendrils of mist. At 9:45 the strings reminisce on the very start of the work and prepare the way, with gentle striving, not for a sunrise but for a thoughtful fading away. The message seems to be not quite despair, not quite contentment. The music speaks of something chastened, cool and brooding.

I suspect that the cinematic world in which Berkeley was steeped at the time had its effect on Nocturne: his scores in that field included the recently televised Hotel Reserve (1944) and other films such as the shorts: Sword of the Spirit (1942), Out of Chaos (1944), and The First Gentleman (1948).

The Nocturne was premiered at the Proms in the Royal Albert Hall on 28 August 1946 by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Adrian Boult. Beecham appears to have conducted the work on 17 December the following year, although I have not been able to verify this. While it can hardly be said to be a concert staple, or even a frequently broadcast fixture, the work has had its radio moments. The BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra under Raymond Leppard featured it in Part I of their Midday Concert on 1 March 1974. Simon Joly and the Ulster Orchestra included it in a Matinée Musicale programme on Radio 3 on 28 March 1984, repeating it with Barry Wordsworth on 4 May 1989, and again on 16 December 1991.

The performance by which I came to know the Nocturne was much earlier – on 9 April 1976, late one evening, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Vernon Handley. There it shared a determinedly unfashionable programme with the first broadcast of Anthony Milner’s Midway, a cantata for soprano (April Cantelo) and chamber orchestra and Bliss’s Meditations on a Theme by John Blow.

Berkeley clearly had quite a thing for the Nocturne form, or music driven by night-time connections: the Divertimento in B flat has a second and slow movement which bears the title ‘Nocturne’, the set of three pieces for two pianos published by Chester’s in 1938 has a central Nocturne, and 1967 brought a Nocturne for solo harp. From the other end of his life there is another isolated night piece, Voices of the night op. 46 (1973) written for, and commissioned by, the Three Choirs Festival where it was premiered by the CBSO directed by the composer.

That said, the 1946 Nocturne seems, from our perspective, to be a road not taken – or, more accurately, and sadly, a road rarely frequented. It should be revisited more often, for it has a distinctive grip on the imagination.