Lennox Berkeley and the Latin Mass

Julian Berkeley writes about his father’s fight to save the Latin Mass after the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

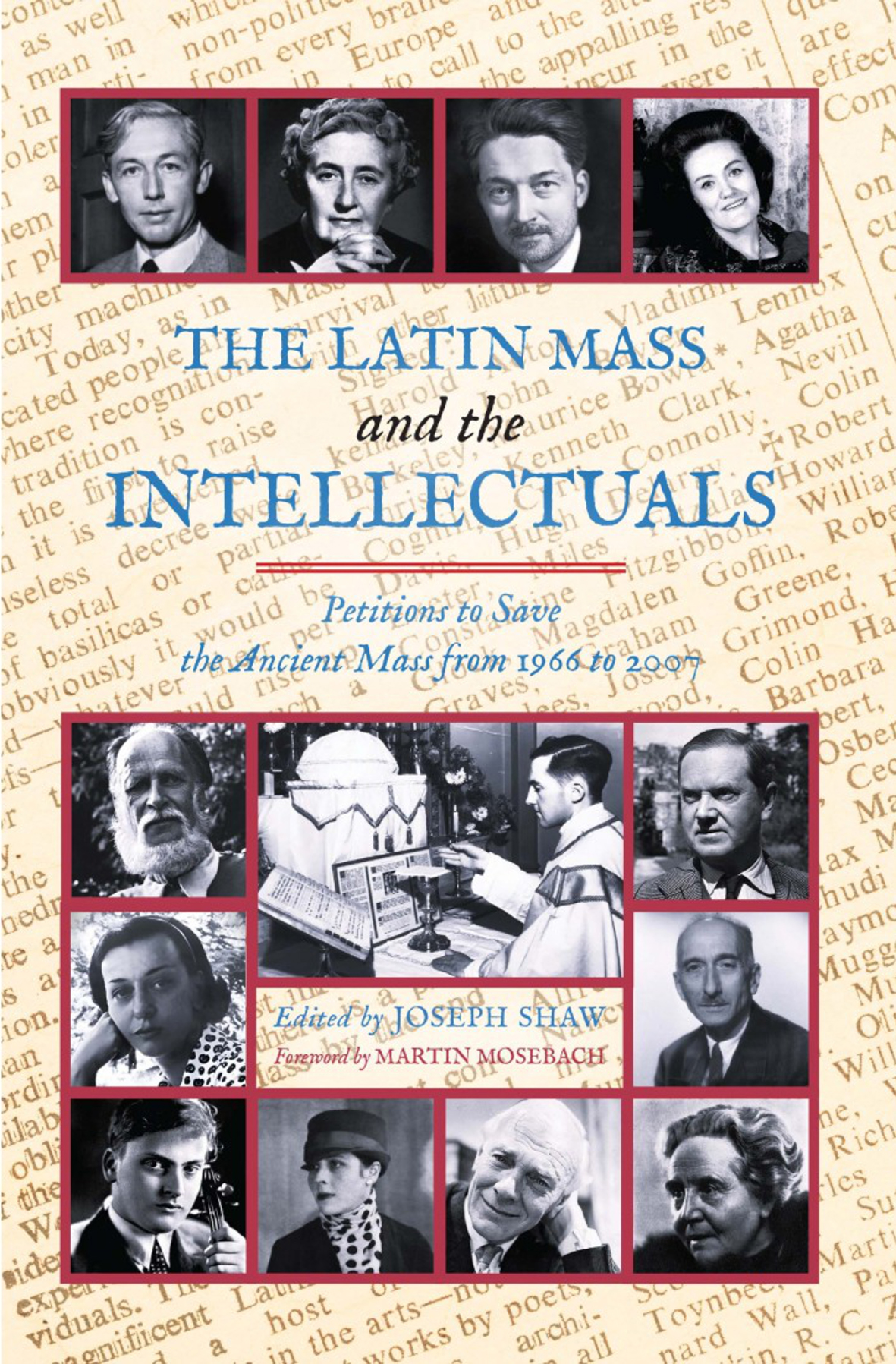

Last July I was approached by the pianist Matthew Schellhorn, a contributor to a new book about the various petitions to save the traditional Latin Mass. He had read my article in the LBS Journal 2008, My Father and his Faith, and wanted to quote from it in his Vox Musicorum chapter in The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals - Petitions to Save the Ancient Mass from 1966 to 2007 [Waterloo, Ontario, Arouca Press, 2023, 410 pp.].

My article had appeared in the wake of Pope Benedict XVl's historic move to safeguard the traditional Latin Mass by means of his moto proprio, 'Summorum Pontificum' (2007). A mere 14 years later – and with Benedict living in retirement – his successor, Pope Francis effectively reversed Benedict's ruling by issuing his moto proprio, 'Traditiones Custodes' (2021). My piece had explained how Lennox would have rejoiced to know that the Mass which he loved and defended was at last saved from the threat of extinction. By contrast, this new article laments the current threat to its survival.

Back in 1971 Lennox was a signatory to a petition, published in The Times, and addressed to the Vatican, which made a direct appeal for the preservation of the traditional Latin Mass. This petition was remarkable in that the signatories were not clerics and not necessarily Catholics; they were 'entirely ecumenical and apolitical ... drawn from every branch of modern culture in Europe and elsewhere'. This wide cast of characters gives rise to the title of the new book, The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals. The petition was successful, at least in relation to England, and Pope Paul VI introduced what became known as the 'English Indult' to permit celebration of the ancient Latin Mass.

Pope Francis has now moved the clock back, not just to the situation pertaining before Benedict, but - in relation to England - by some 60 years, to the the reign of Paul VI and the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council.

The Editor, and major contributor to The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals, Joseph Shaw, has discovered an article in the Italian newspaper L'Espresso which appeared the day after the publication of the petition in The Times of 6 July 1971, based on interviews with six of the petitioners, including Lennox. All six interviews are reprinted in the book, but here is Lennox’s, translated into English, under the paper’s own introduction:

One hundred European men of culture, including some well-known progressives, have asked the Pope to restore the traditional Mass. Why? We asked them directly. The musician – Lennox Berkeley.

‘I find that there is a cultural value in a rite that has been celebrated for so long and that has close connections with art, especially with music. If Latin is abolished in the Mass, that also abolishes Gregorian chant, which is sung in Latin. Also, the current English translation of the Mass is not good, I think everyone agrees on that. It seems to me that the translators have tried to turn the text of the Mass into a sort of colloquial English, but I think that the liturgy needs a language of its own, not the popular English that has been used here, which is unlikely to inspire prayer or music. The purpose of the Church has, rightly, been to enable people to understand and follow the Mass more easily. But it often happens that, when you begin to change, you are seized by a frenzy of total demolition. Some point out that the ‘Tridentine Mass’ has not existed for a very long time and that in recent years there have been numerous liturgical modifications. But that is not true. There were indeed changes in the Mass from the time of the Apostles up to the time of the Council of Trent, but virtually none since the sixteenth century. The ‘Tridentine Mass’ has been the universal Mass since 1570 and no one has ever been authorised to change a single word of it in the last four centuries. Personally, I do not believe that these changes were necessary. I therefore hope our appeal will be effective’.

In his Foreword to The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals, the distinguished German writer, Martin Mosebach, says the book 'describes the battle for the Roman liturgy, for the Church's two-thousand-year-old tradition’. Those who fought it, he writes, ‘were convinced that it was the most important battle of the twentieth century, with its devastating political upheavals and wars that devoured nations’. For a Catholic, this battle, he maintains ‘is indeed more important than the fight against totalitarian ideologies, more important than the multifarious attempts to protect the natural world, because it was and still is about the continuity of the Christian religion itself, which has been damaged in a life-threatening way’.

The book examines the context of a number of petitions seeking the preservation of the traditional Latin Mass and addresses the reasons why so many leading figures, across a wide cultural spectrum, felt sufficiently strongly to become involved with the campaign to limit the damage being inflicted upon it. The signatories were acutely aware that its disappearance would leave a gaping void in our culture and civilisation.

One of 'the Intellectuals' to sign the earliest petition (in 1966) was my father’s Oxford friend, the poet W. H. Auden, who – along with the composer, Sir James MacMillan – is included in a chapter called Modernists Against Modernity. Lennox was drawn to Auden's series of poems, Horae Canonicae, inspired by the hours of the Divine Office, and he chose one of them, Lauds, to open his Five Poems (Op.53).

For Lennox, and innumerable others, a great attraction of the traditional Mass was its immutability. It had remained free of the whims of fashion over a great many centuries, but by the 1960s it was suddenly being exposed to the harsh iconoclasm of modernity, largely in the mistaken belief that a modern world required a modern liturgy. Unfortunately the modern world was not captivated by the new vernacular rites and a mass exodus followed.

If there is a flicker of hope, it lies with the small number of traditionalist communities which have been exempted from the strictures of Traditiones Custodes. Among them are those Benedictines who have chosen to remain faithful to the traditional Latin liturgy in the Abbeys of Fontgombault and Le Barroux, in France, and Clear Creek in the USA, and in the new monasteries of Silverstream in Ireland and Notre Dame in Tasmania. Outside the cloister, there are priestly associations which exist specifically to maintain the traditional teaching and liturgy of the Church, such as the Fraternity of St Peter (FSSP) and the Institute of Christ the King (ICKSP). Added to these must be the society of priests which has remained outside the direct control of the Vatican since its foundation in 1970, the Society of St Pius X (SSPX).

All these groups are drawing in new generations of young people who are eager to discover the transcendental world of the ancient Latin Mass. The demand is such that the SSPX has built new churches for its celebration in the USA and, most recently, in the UK at St Michael’s School, Burghclere.