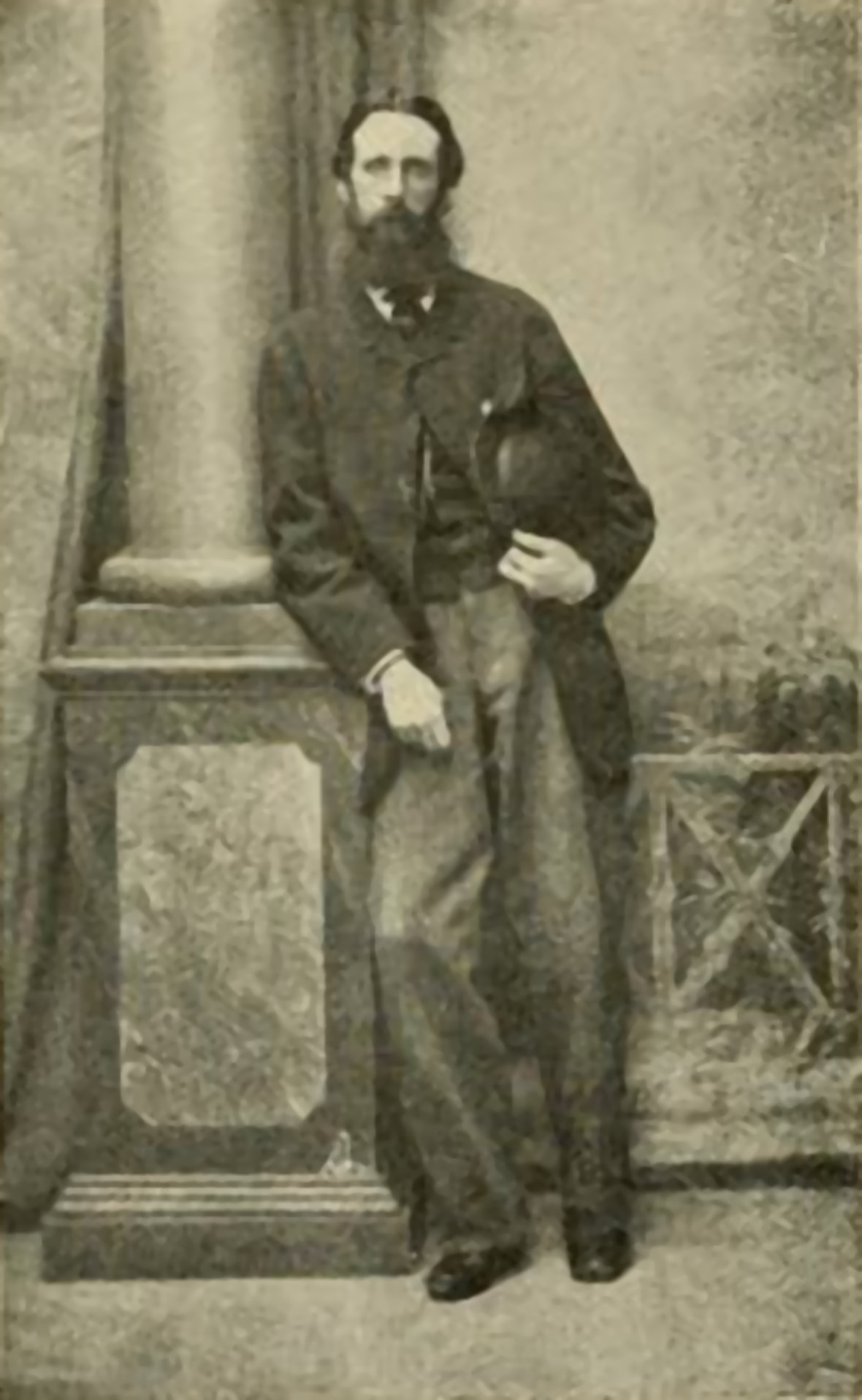

The 7th Earl Of Berkeley, Gambler And Musician

Tony Scotland on the 7th Earl of Berkeley, Lennox Berkeley’s bohemian grandfather

In my book, Lennox & Freda,1 I gave a brief account of the life of Lennox’s paternal grandfather, Captain George2 Berkeley, later 7th Earl of Berkeley, which touched on the double blight he bequeathed to his two eldest sons (Captain Hastings Berkeley RN and Sir Ernest Berkeley): their illegitimacy, and his bankruptcy. The illegitimacy was caused by his inability to marry their mother, Cécile, until the birth of their brother Randal, because she was still then married to Admiral the Hon. Sir Fleetwood Pellew. As for the bankruptcy, I speculated that this was caused by a chronic addiction to gambling. In a series of Edwardian memoirs, recently unearthed online by the Lennox Berkeley Society’s joint founder and indefatigable internet sleuth, Kathleen Walker, it turns out that my guess was only too correct – but that there was more to the 7th earl than gambling.

In the late 1870s, by which time they had been married for more than a decade, and were flitting across Europe in pursuit of gambling rooms, George and his long-suffering wife Cécile were staying in the Hôtel de Russie in Frankfurt. According to an anonymous ‘English Army Officer’, who was then a young Etonian staying with his parents in the same hotel, the games of trente et quarante and roulette were all the rage at the time, and George Berkeley was eager to play, but unfortunately he had already lost all his money at the tables in Hamburg. So be begged a banker friend to lend him two thousand florins. Knowing Berkeley’s circumstances, the banker friend refused, but kindly gave him instead a ticket for a local lottery.

A fortnight afterwards the lottery was drawn, and he [Berkeley] won the gros lot [the jackpot] of seventy-two thousand florins, or six thousand pounds [the equivalent of more than £250,000 today]. Next day he gave a supper to all the members of the English colony, which piece of hospitality cost him two thousand florins, and he lost the rest at the tables of Hamburg six months later [where, first, he broke the bank, and then he lost all that he had won and more].3

Not long afterwards the Berkeleys were staying at the Belgian resort of Spa, in a valley of the Ardennes mountains near Liège. They were supposed to be taking the waters, but the Etonian alter ego of the same military source, who seems to have been haunting Captain Berkeley, reports that he was more often to be found at the gambling table, and that he had as little luck there as in Hamburg. What the informant (much later identified as George Greville Moore) does not explicitly state is that his own father seems to have been no less addicted to gambling, which is why they all kept bumping into another all over Europe towards the fin de siècle. Again in Brighton, where the Berkeleys took a house in Regency Square one summer in the early 1880s, the same group of hardened old gamblers had a grand and expensive reunion, reminiscing about their systems at the tables, and deploring their heavy losses. George Berkeley is quoted as regretting that he had ever gambled at Hamburg at all, because it was ‘foolish to try to make yourself believe that you can ever win’ at gambling, ‘but there is an attraction there that somehow one cannot resist’. They all said they had given up playing roulette and trente et quarante now, but admitted they still played at baccarat and the Stock Exchange.4

The three volumes of Moore’s memoirs which provide the (entirely uncritical) evidence of George Berkeley’s gambling addiction, also record some of his happier traits. We learn, for example, that ‘he was one of the nicest Englishmen in Paris [in the late 1870s]’5, and that he was unusually charitable:

One Sunday evening, I went with Captain Berkeley to see some fine illuminations in the Champs-Elysées. I recollect telling him how much I disliked a crowd, to which he replied: ‘It is the only day on which the poor people can enjoy themselves, and they have as much right to do so as the rich.’ One day a beggar came up to him and asked for some coppers, upon which he said, ‘Mon cher ami, c’est défendu de mendier, mais voici un franc; ne le faites plus.’ [My dear friend, it’s forbidden to beg, but here’s a franc; don’t do it again.]

He was also an accomplished letter-writer, particularly – perhaps perforce – of business letters. None of the circle of George Greville Moore’s father, all of them as addicted to gambling as their noble friend, ever put pen to paper without first consulting George Berkeley.6 It helped that he was a fine linguist too – especially proficient in French. Moore said he ‘never heard an Englishman speak French so beautifully ... without any accent at all’.7

But the characteristic that is of most interest to us is that he was ‘passionately devoted to music’, and played several instruments.8 One of them was the zither – not the Tyrolean peasant zither, but the streich melodion or viola zither, played on the lap with a bow.9 It was popular at the time in Vienna, where thirty or forty were played together by a popular band formed of beautiful, well-born young women. George Berkeley took up the instrument after he had inherited the earldom in 1882 and was living in Paris with his wife Cécile and her sister, Albine, baronne van Havre, in the rue de Saint-Pétersbourg in the newly developed quartier de l’Europe. His teacher, who gave him lessons at home every evening, was the Italian violinist Vincenzo Sighicelli, who had been soloist and assistant conductor of the Este court orchestra in Modena.10

The violinist Berkeley most admired was Paganini’s favourite pupil, Camillo Sivori, who played on a violin given by Paganini himself, a copy by Vuillaume of the great master’s own Guarnerius. Berkeley told the ever-attentive reporter George Greville Moore that he preferred Sivori because he ‘played with so much feeling and eschewed those complicated pieces which resemble gymnastic exercises for the fingers’.11

The Berkeleys used to give musical soirées at which principals from the orchestra at the Opéra took part. Among them was the virtuoso flautist Paul Taffanel, who was celebrated not just for his phenomenal virtuosity but also for the full tone of his silver flute’s lower register, and for his light vibrato. Occasionally Sighicelli would appear too, and entertain the guests with his own fantasies on operatic airs.12 Often there was singing too. One of Berkeley’s favourite singers was his friend the Marquise Brian de Bois-Guilbert, a pupil of the tenor Gibert Duprez (the original Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor), who sang operatic arias in a voice with a range as wide as Malibran’s, and told affecting stories of the exploitation of professional musicians. Some rich Parisian friends of hers, she said, had once invited two singers from the Opéra to dinner, in the hope that they would sing afterwards for nothing. But the two singers knew the trick – and bettered it: when they had finished their dinner they each put a louis on their plates and left for home without singing a note.13 Mme de Bois-Guilbert (who was probably the wife of the London theatre manager, Alfred de Bois-Guilbert) had been a great beauty but was now, though only thirty-five,‘a little passée’; she ‘made up a great deal’, according to Moore, who missed nothing, ‘and wore very décolletée dresses’.14

George Berkeley had his own stories about the trials of artists. According to Moore, he would often remark that the English are particularly insensitive to music, and talk when anyone sings or plays. Berkeley told the story of how Paganini was once playing a solo ‘and had reached the most pathetic part’, when he was suddenly interrupted by an English peer who touched his arm and said, ‘Pardon, Monsieur, mais j’ai besoin de causer avec une dame’ [I need to have a word with a lady]. Milord had then raised the maestro’s bow and passed underneath towards the lady in question. ‘Si ce ne’est pas vrai’, said Berkeley, ‘c’est très bien trouvé’. [If this story isn’t true, it’s very well found.]15

As I recorded in my book, George Berkeley died at Brown’s Hotel in Piccadilly on 27 August 1888, aged sixty-one. He left a gross estate of £56 16s. 2d., which he bequeathed to his two elder sons - Lennox’s father, Captain Hastings Berkeley, and Sir Ernest Berkeley. But neither saw a penny of it, because Lord Berkeley died an undischarged bankrupt and his assets were seized by the courts as a sop to his creditors.