Lennox Berkeley 'Oboe Quartet' for Janet Craxton

John France examines the context of Lennox Berkeley's 'Oboe Quartet' of 1967

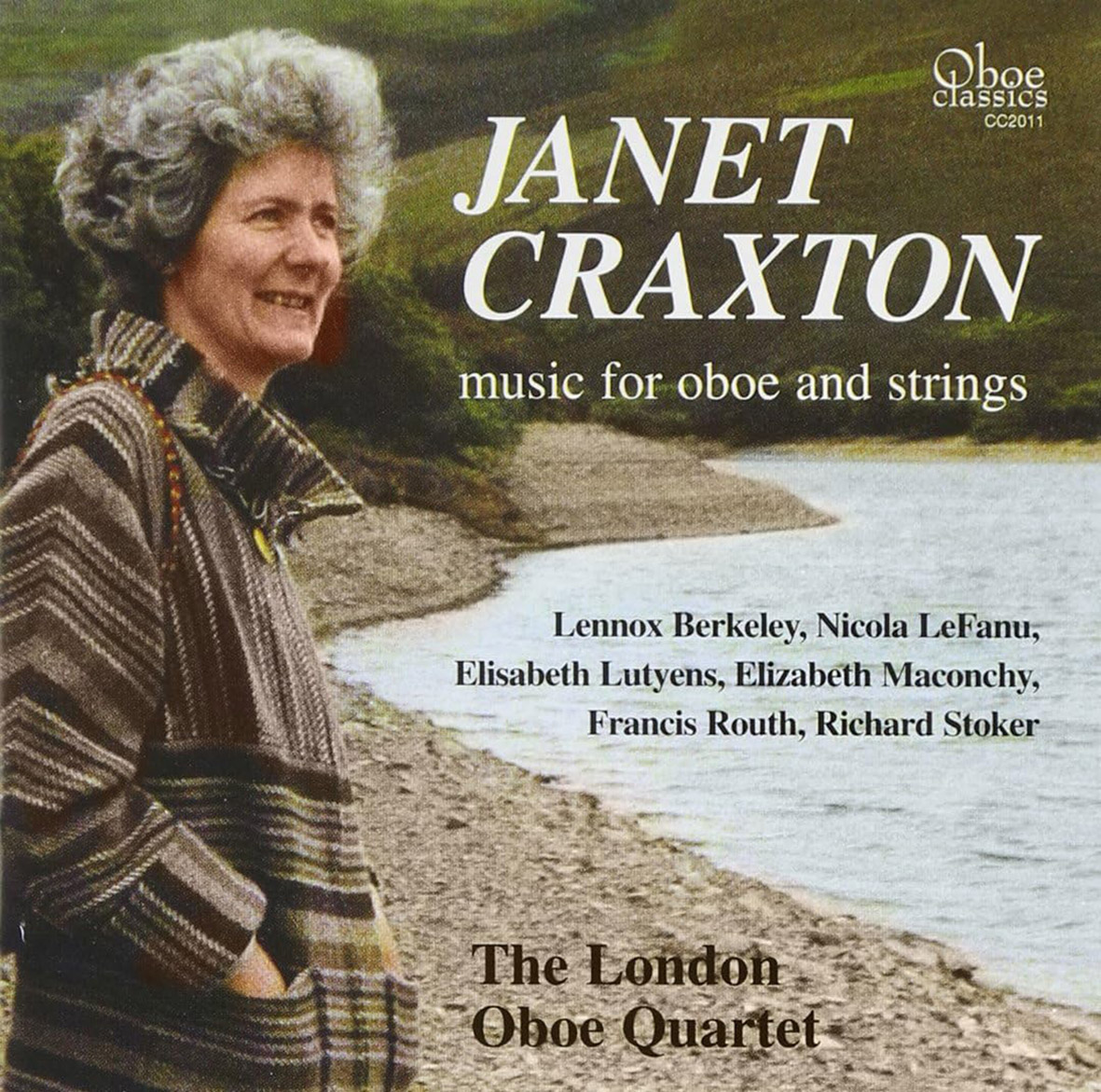

Many years ago, I came across the miniature score of Lennox Berkeley’s Oboe Quartet in a second-hand bookshop. It cost 25p, which seemed to me a sound investment, for future reference. Back then, I had not heard the work in the recital room, or on record. Some years later, I had the privilege of reviewing a retrospective CD of music for oboe and strings played by the legendary Janet Craxton. Amongst works by Elizabeth Maconchy, Richard Stoker and Elizabeth Lutyens, I finally discovered Berkeley’s quartet. I noted in my assessment that it was ‘by far my favourite piece on this CD’. And this is not surprising. It was certainly the most traditional number on the album: it does not have a programme or rely on overt serialism. In fact, it exploits a tonal language which nods more to the neo-classical style of between-the-wars French composers, than the followers of Webern and Schoenberg.

Lennox Berkeley wrote several works with Janet Craxton in mind. In 1962, the Oboe Sonatina op. 61 was dedicated to her and her brother, the painter John Craxton. Eleven years later, he was commissioned to write a large-scale concerto to be premiered during the Proms Season. The five-movement Sinfonia Concertante, op. 84 for oboe and orchestra was duly performed at the Royal Albert Hall on 3 August 1973. Janet Craxton was the soloist, with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra conducted by Raymond Leppard.

The Oboe Quartet was commissioned by Lady Norton (Nöel Evelyn Hughes), on behalf of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, and dedicated to her, but composed with Craxton in mind. Berkeley began writing during September 1967, and finished it two months later, on 30 November. 1 In June of that year, the premiere performance of his opera, Castaway, had been given at Aldeburgh. Another first performance in 1967 was Signs in the Dark presented at the Stroud Festival – settings for choir and orchestra of poems by Laurie Lee.

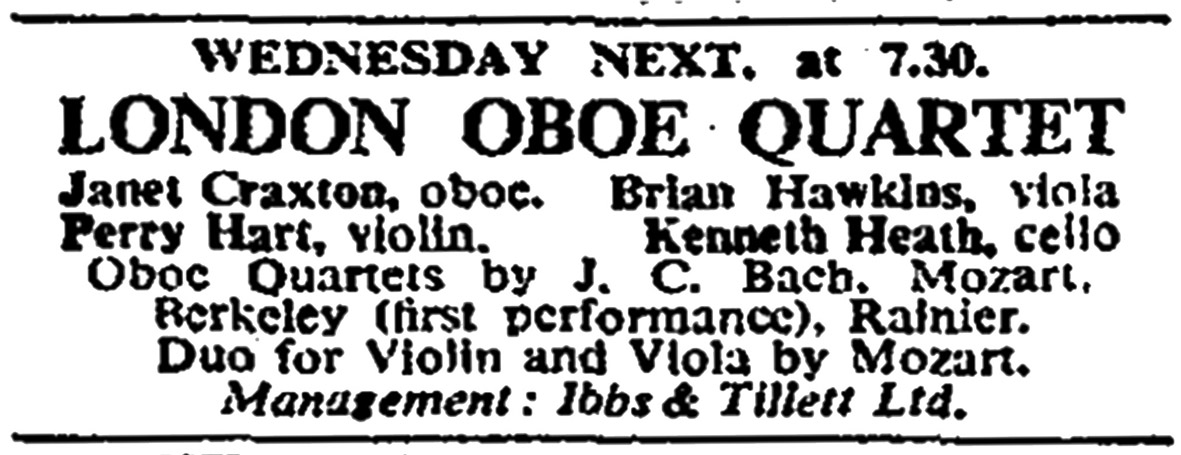

After completion of the Oboe Quartet, Berkeley began composing his Magnificat for the following year’s City of London Festival. In May 1968, he travelled to Monte Carlo for a three-week stay, returning to London in time for lunch with Queen at Buckingham Palace on the 22nd, 2 and the premiere of the Oboe Quartet at the Wigmore Hall, London, in the evening. The performance was to have been given by the Oromonte Trio, but unfortunately this ensemble was disbanded before the premiere, and so it fell to the London Oboe Quartet to fill the breech. 3 Janet Craxton had founded this group, with Perry Hart (violin), Brian Hawkins (viola), and Kenneth Heath (cello), specifically to play the new quartet. 4 They went on to give many more concerts and radio broadcasts, and to commission several new works for their forces.

The Wigmore programme for the premiere of the Berkeley quartet also included J. C. Bach’s Oboe Quartet in B flat, Mozart’s Oboe Quartet K.370 (1781), his Duo for violin and viola, K.423 (1783) and his Adagio for Cor Anglais and String Trio K580a (1789). There was also a performance of Priaulx Rainier’s Quanta for oboe and string trio (1962). Although there is a recording of this latter piece, it has failed to remain in the repertoire.

The following day Joan Chissell, writing in The Times, considered that the programme was well thought out. The London Oboe Quartet had been ‘wise’ to end the recital with Mozart’s quartet, which was ‘still [the] finest item’ in the oboe and string trio repertoire. In Chissell’s view, Berkeley’s ‘ambitions, and [the] emotional range of his music, have always been restricted’. The present work was enjoyable, she thought, but said little that was new. The craftsmanship, however, ‘remains as precise as ever and lyrical grace is nowhere lacking’. Interesting too are Chissell’s thoughts about Rainier’s Quanta, which, she said, with its ‘austerely characteristic, offering [of] endless rhythmic invention as a vehicle for terse, concentrated motivic development’ offered a striking contrast to the Berkeley. 5

John Warrack, in the The Daily Telegraph, considered that the Berkeley quartet was ‘superficially a modest but by no means therefore a negligible piece.’ The first movement was ‘the least precise’, but ‘the scherzo has a real rhythmic energy a long way from the routine skittishness of so many similar oboe movements, and the finale provides an exact balance in its poised tenderness.’ Like many critics of Berkeley’s music, he acknowledges the quartet’s ‘real craftsmanship … in understanding not only what will simply sound well on the oboe … but [in] the emotional weight this ensemble may bear’. Warrack concluded appositely: ‘After so many works, by quite eminent figures, composed in the evident belief that the oboe can only be played by manic depressive shepherds, it is satisfying to have a work by a composer who has really listened to the medium and recognised what of himself can be found in it.’ 6 Perhaps he was alluding to Priaulx Rainier’s unsmiling offering?

On the last day of May 1968, Lennox Berkeley confided to his diary: ‘First performance of my Oboe Quartet. I’ve never had anything of mine played better. It is a first class ensemble and Janet [Craxton], of course is an outstanding musician.’ 7

His Oboe Quartet is in three movements, lasting less than fifteen minutes. The first begins with a long, morose Moderato introduction. This is followed by an Allegro that balances reflection with a little angst, presented in largely traditional sonata form. The Scherzo, a presto, is much more exciting – lots of interesting writing here – with pizzicato strings, and intricate arpeggios and scalar passages for the oboe. It eases off into a kind of trio before the movement finishes with a curtailed recapitulation of the ‘fast’ opening. The finale, an Andante, is the heart of the work – even if it comes, unusually, at the end. It is deeply thoughtful and in complete contrast to the preceding Scherzo. This songlike music just seems to fade away, but with the last word (or note) being given to the cellist. As far as Berkeley uses imitation and thematic inversion, this quartet nods towards the kind of serialism that he had adopted in the early 1960s. Yet, there is no tone row: the building block of the entire work is the interval of a major or minor third (e.g. C-E or C-Eb).

It is not within the scope of this essay to provide individual reviews of the current CDs of Berkeley’s Oboe Quartet. Nevertheless, it will be instructive to examine a couple of critiques of Janet Craxton’s recording of the premiere performance. In 2005, Oboe Classics issued this in an album featuring six British works for oboe quartet, played by Craxton and the London Oboe Quartet (See Discography below for details). Andrew Achenbach in The Gramophone noted that ‘Craxton’s impeccable technical address, naturalness of expression, recreative flair and subtlety of nuance are an absolute joy throughout: what a wonderfully eloquent, selfless performer she was!’ 8 Equally enthusiastic were Valerie Taylor’s comments in the Double Reed News : ‘In all these wonderful quartets, I admire the range of musical expression, intense musicality, tone colours, control (particularly Janet’s control of diminuendos), intonation over huge intervals as well as fluent finger technique and immaculate tonguing … The quartets become so alive with the interplay between the oboe and the string players, and the ensemble throughout is impeccable.’ 9

The prime characteristic of the Oboe Quartet is the immediately obvious workmanship. This applies to the formal structure as well as to the fluency of the instrumental writing for the oboe and the strings. The critic Peter Pirie sees the quartet as ‘a gentle essay in absolute music – no depths need be expected, but it is a lovely short work.’ 10 I disagree. There is an intensity and strength in it that goes beyond the merely entertaining.

Finally, Desmond Shawe-Taylor, writing in The Sunday Times, was correct in concluding that Berkeley’s Oboe Quartet presents a ‘crescendo of interest’, from the first movement that ‘seemed grey as if pointedly excluding surface charms’, through the second which is ‘a neat and witty scherzo’, to the finale which introduces ‘a warmer note with its subtle manipulation of a rocking theme.’ 11 A perfect summary.

Discography

Lennox Berkeley, Oboe Quartet, Sonatina op. 39; Sextet op.47; Diversions for eight instruments op.63; Palm Court Waltz; The Nash Ensemble, Hyperion Records, A66086, LP (1983); CDH55135 (2003).

Lennox Berkeley, Oboe Quartet, Introduction and Allegro op.24; Elegy op.33 part 2a; Toccata op.33 part 3; Sextet op.47; Concertino op.49; Duo op.81 part 1; Petite Suite ; Melinda Maxwell (oboe), Endymion Ensemble, Dutton Vocalion, CDLX 7100 (1999).

Lennox Berkeley, Oboe Quartet, with music by Francis Routh, Nicola Le Fanu, Richard Stoker, Elizabeth Maconchy and Elisabeth Lutyens; Janet Craxton (oboe), The London Oboe Quartet, Oboe Classics, CC2011 (2005).

Lennox Berkeley, Oboe Quartet, String Trio op.19; Sonatina op.61; Suite ; Trio ; Sarah Francis (oboe/cor anglais), Michael Dussek, (piano), Judith Fitton (flute/piccolo), Tagore String Trio, Regis Records, RRC1380 (2011).